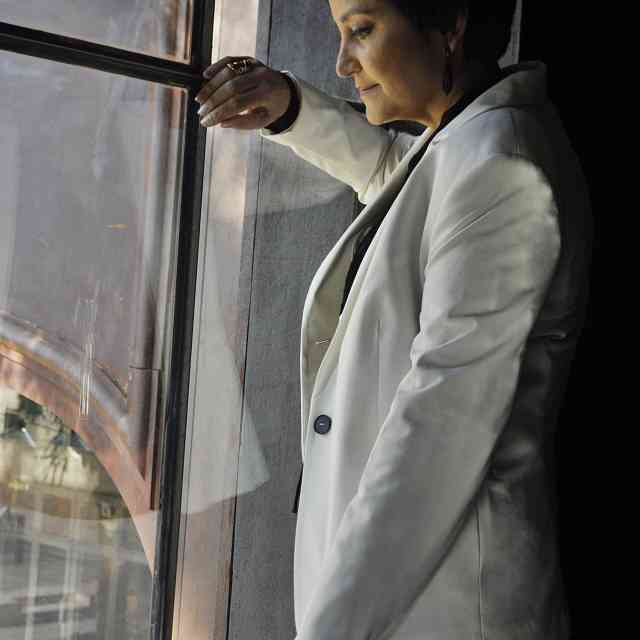

Scott Tennant

This unique interview is a sort of a cyber-roundtable of questions for guitarist, teacher and technical guru Scott Tennant. Scott is a founding member of the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet, an amazing soloist, and the author of what has become the current leading technique manual for classical guitar, Pumping Nylon. Scott is featured on our Suzuki Guitar Method Book Nine CD and he has taught quite a number of Suzuki kids in his travels.

For this interview, emails were sent to Suzuki Guitar students and teachers to learn what they would like to ask Scott. What follows are questions we came up with together. I would like to thank those who responded to my request: Maxwell Miller (Houston, Texas); Jason Short (Columbus, Ohio); Gene Swenson (Humble, Texas); Austin Wahl (Rochester, New York); Eric Ulreich (Leesburg, Virginia).

Scott, we are very excited that you’re coming to our Suzuki Conference 2016!

Thanks, I’m excited too. It’s my first time to attend.

How did you choose guitar as your instrument and how old were you when you started playing?

My brother and I received toy guitars for Christmas since I was three or four years old. When I was six, I got my first real guitar—a little steel-string. My mother told me I had to take lessons, so I grudgingly did.

And how long did it stay “grudging” for you?

My mom made me practice 15 minutes a day and she sat there while I did it. I knew my friends were outside, so at first it was painful. After a few months, I was enjoying it more—when I started to see some progress.

Was anyone in your family musical? Did anyone play the guitar?

Mom was musically inclined. She played woodwind instruments all through junior high and high school. My father loved listening to music.

I found guitar very fascinating—anything with strings on it, I was interested in it. Guitars, little toy banjos—that is why my brother and I received them as toys every year.

What artists other than guitar players have influenced you and why?

That is a really good question!

Growing up, I was influenced a lot by visual art too. The illustrations in Dr. Seuss’ books I found fascinating. I learned that we also share a birthday.

For a long time, the only orchestra recording we had in the house was Andre Kostelanetz and his orchestra playing tunes like “Love is Blue.” I thought it was great symphonic music!

We always had recordings of singers in the house. My father was of Scottish descent, so we listened to a lot of Celtic Music—especially singers. This had a great influence on me. Artists like Andy Stewart, Tommy Makem and the Clancy brothers. Another was the TV show Hee Haw which had a lot of string instruments and players—especially guitarist Roy Clark.

Who were your early teachers?

My first teacher was Wanda Bruning, who I studied with at a local music store in Detroit. She was my teacher from age six to eleven. We were using a plectrum and playing through different books. There were little melodies by composers like Tchaikovsky in these books, and I liked those. She told me they were classical music and that there was classical style guitar. She said she couldn’t teach me, but she could help me find someone.

So, after her I went to downtown Detroit and studied with Joe LoDuca, who is now a well-known TV composer, Lee Diamond and others who were all students of Joe Fava. Eventually I auditioned for the Joe Fava Conservatory of Guitar in Birmingham, Michigan. I was 12 or 13 at the time and though he normally didn’t take kids, he took me as a student. I studied with him the rest of my time in Detroit.

I met Pepe Romero when I was 14 going to Houston, Texas, for his master classes every summer. On his suggestion, I began flamenco studies with Juan Serrano, who was living in Detroit at the time. For college I attended University of Southern California where Pepe gave lessons. A bunch of us also went to his house for lessons, too.

While living in Detroit, my master class teachers included Alirio Diaz, Oscar Ghilia and

Michael Lorimer—who came out every year, so I studied with him a lot. At USC, I played for David Russell, Paul Odette, Manuel Barrueco and many others.

Who would you say were your most influential teachers?

That would be Pepe and Juan Serrano.

What are some of your favorite pieces, especially from your early years?

My favorite pieces as a kid were all the pieces my teachers didn’t want me to play! You know, all the really hard pieces. I would get the music and see that they were too hard, but then do them anyway. And honestly, I still have psychological blocks on those pieces because I started them when I technically wasn’t ready. Some of them, my teachers never knew about. The Bach BWV1006, Fourth Lute Suite Prelude is still one of my favorites and still one of the most scary for me to play because I started it almost immediately when I started classical guitar. Asturius/Leyenda of course, which I had great fascination for and still love to play. The Aranjuez Concerto second movement. I’ll say it was anything that was on this album of John Williams—The Best of John Williams. It had the Granados Dance Number 5, the Adagio from the Aranjuez, Paganini Caprice 24, some Praetorius—anything that was on that recording were my favorites and still are today.

What are some of your favorite places to visit?

I’ve seen everything except Africa at this point, and though I’ve never lived there, London feels like home to me. I was going to go to school there until I found out Pepe Romero taught at USC. Growing up watching British comedy, which I enjoyed, contributed to my interest. I would have ended up at the Royal Academy there. I love the atmosphere, and it’s still my favorite place to visit.

Edinburgh is probably my second favorite—it’s an amazing city. Of course being of Scottish heritage on my father’s side, I have a great appreciation for that. Also I like bagpipes and everywhere you go as a tourist, there’s one on every corner, which is great.

There are many others, too. I also love Spain culturally and because of its origins with the guitar.

How did your interest in flamenco evolve? How would you say it helped in shaping your career as a performer?

I studied flamenco with Juan in Detroit for a couple of years before he moved to Fresno, California. He had played for the classes of Maria del Carmen, who was a flamenco dancer and teacher. When Juan moved away, I got to be the one to accompany her classes. Eventually, it led to me being listed as the guitarist on the performance bill.

Really, that is the best way to learn flamenco—by watching dancers. It did shape my technique and my career outlook. It helped me appreciate Spanish music in a very special way. I could approach it not only musically, having played flamenco and from the experience of watching the dancers, but also in a technical way, too.

Writing a book on the level of Pumping Nylon takes years of development and a lot of time-consuming work. Since the book effectively filled a void in classical guitar pedagogy, what did you feel was missing in current study and what inspired you to write it?

I never intended to write a book. I had compiled—as all teachers do—a bunch of exercises that I would give my students that really weren’t in any book. They were not all mine, some were from flamenco and some from Pepe. I kept all of those sheets of paper and year after year, the pile grew. The Shearer book really helped explain how the fingers moved, but there wasn’t any book that I had found that was thorough enough with application. Eventually, I thought, what if I try to put these together?

I called Nat Gunod, who I knew from the Summer Workshops. He had just signed a deal with Alfred Music, so he immediately said yes—he was very interested. So I got started and it took two years. I had just switched over from a word processor, which I thought was real high-tech, to my first Apple computer. It took me forever to write the book on that thing. That plus a lot of it by hand. I honestly thought nobody would buy it and that I would just use the copies for my students.

Just last week, in fact, we finished the second edition. It will be out early next year. It’s basically the same core material with some added etudes, some more instructional text and much, much better video.

So, it will be out in time for our Conference in May?

Yes, that’s right, it will!

Do you have any non-traditional sounds (other than Bartok pizzicato) that you like to use?

Absolutely! Since guitars are built more like drums with a wooden skin (a banjo is a drum with strings), I/we use the top and sides of the guitar to get sounds like a bass drum, castanets, clave, and if you cross two strings and hold them down with the left hand, you get a snare drum effect. There are other percussion sounds, but those are the main ones.

The quartet also employs the use of alligator clips and little plastic discs on exact parts of the strings to sound like a gamelan orchestra (look up “Gongan” played by LAGQ on Spotify), and I use staples that I bend and attach to make it sound like an mbira (also look up “African Suite ‘Mbira’” by LAGQ).

Now I would like to ask for your thoughts on Suzuki Guitar as a method and a movement of a sort. At this time, we are beginning to see some of our earliest students, such as Connie Sheu and Adam Kossler, complete the doctoral level of study and place in international competitions. In recent years, several students with significant training in Suzuki Guitar have taken top awards in the GFA Youth Competition and many other contests as well. Certainly, excellent young students are also trained with other methods, but do you feel Suzuki guitar has made a unique impact?

Certainly it has. I know Connie Sheu well—she did her doctoral degree at USC. Also just two blocks away from me is the Pasadena Conservatory that has an amazing Suzuki program with all instruments, including guitar. The guitar program is headed up by Felix Bullock and has about 100 guitar students.

I have no Suzuki training myself; my role there is listed as master teacher. I do master classes where they play for me and I give each of them a lesson once a semester. I think these kids are amazing. It’s really refreshing to give musical or technical advice and see them just do it. They just soak it up. There are no analytical barriers built up yet, so, for me, it’s a lot of fun.

Well, that’s great to hear. And now I would like to ask about your thoughts on the future and where you envision the classical guitar twenty years from now?

The future of the guitar, well, I believe classical guitar is always going to flourish. Guitar is the only instrument that is completely cross-cultural. You see it in every culture and many ancient cultures have adapted it and made it their own. Examples I can think of are Indian Ragas and Hawaiian slack-key guitar. In Africa, there are many different styles of guitar music. It’s just the most popular instrument in the world. It does seem that everyone has tried or wanted to try playing guitar at some point. I haven’t met anybody who doesn’t like guitar. That can’t help but continue. So, I believe the future is bright.

Now, things have changed a lot since Andres Segovia and the early days of modern classical guitar. Julian Bream invited many different composers to write for the instrument. People are still writing for the guitar today, but the world of composition has changed as well. There don’t seem to be super-stars anymore like Stravinsky. Back then, Leonard Bernstein had a TV show for kids, and you just don’t have anything like that anymore. The popularity and attention on composition has shifted quite a bit. Artists like David Russell or Manuel Barrueco will have works written for them. However, the premiers do not seem to have the same weight now as they did back when Bream was playing new works and the idea of classical guitar as a concert instrument was still fresh.

We have actually folded ourselves into the world of concert instruments now and we are very respected. I think there will always be little pockets of those who think differently since it’s not an orchestral instrument. Guitar is always going to be seen as having a folk element. All things considered, I think the future is very bright; I’m extremely optimistic and very positive about it.

Our Suzuki Guitar Studios are filled with school-aged kids. Typically, master teachers such as you have a lot to say to our advanced and dedicated teen students, especially those considering music as a college major. What advice would you offer to the students who are playing very well, but who are not old enough to have made a decision or are older, but are not considering music as a career?

That’s a good question because I know this is true of the kids at Pasadena Conservatory. They get an amazing education there and a lot of them do continue and audition for college, pursuing higher education in music. Then, there are others who enjoyed their instrumental studies, but want to go on to medical school or get a business degree. That does not in any way degrade the education they’ve gotten which is going to last them a lifetime. So having said that and thinking now of the younger kids, something I would give as advice to them is that I think it’s important that they find something that they love in music and be able to apply that to playing the guitar. This is tough because I don’t want to sound like my dad saying, “You better do this now because in a few years time you’ll want to be doing that…” At such a young age, they don’t relate to “in a few years’ time.” I would say that it’s an amazing thing to be able to share your joy of music with people whether it’s on a professional level or not and that they should look forward to sharing all the love and happiness they have received. After all, if it weren’t for the people that taught and shared with them, they wouldn’t have had the fun and enjoyment from it to share with others. And that’s really why we all do it, whether we’re professional or doing it as a hobby.

Dr. Suzuki spoke of the real objective being to create caring citizens—compassionate people with beautiful hearts. We love to see our students that decide to make music their careers, but most of the students we teach remain recreational musicians who have a deep love and appreciation for what they have learned and experienced.

I’ve seen that with the Suzuki Students specifically. Whether they go to college for music or not, they do continue. If it’s not professional, still, in some way, they continue.

They can stay in touch with that love they have for it by sharing it with others. They don’t have to be a professional player. They don’t have to become a teacher. They will continue to love it if they just play a couple of pieces they love all the time for people they love.

Last of all, a non-music related question. One of our Suzuki Guitar alumni has heard of you’re a coffee lover and would like to know why you put butter in your coffee?

Butter in my coffee! Well—it’s not a new concept. Tibetans have been putting butter in their tea for probably hundreds and hundreds of years. I mean, out of necessity, right? They have yak milk and yak butter, so, they put that butter in their tea.

My brother and I both had issues with our thyroids when we were growing up. This idea is mainly for people who are on ketogenic diets. There is a recipe for morning coffee that consists of a very pure, grass-fed, unsalted butter and a little bit of coconut oil.

Supposedly, you drink it in the morning and your energy levels stay consistent.

I’ve tried it, but I don’t actually like it. I drink espresso. I make it here at home. Yep, I make espresso and I just drink it straight.

Well, thank you for entertaining that question. And thanks for your time and wonderful responses in this interview!

No problem! I always enjoy answering coffee questions.