A New Idea

I wonder how thrilling it would have been to be in Dr. Suzuk’s presence as he discovered a revelatory “new idea.” I imagine that some of the best ideas come unexpectedly in a moment of inspiration, perhaps during a lesson, fulfilling a need to communicate something differently, with more clarity, or with a personal connection to a student. Teaching at its best is a collaborative effort, so the “new idea” that forms the basis of this article would not be without my viola student Z Campbell’s questions about left-hand discomfort and tension, challenging both of us to come up together with a simple and effective solution.

When you watch the technical prowess of artist performers, their hands rebalance with ease and fluidity as if their intuition was inborn. Pedagogues like Kato Havas speak of the “giving hand” or the 3–4 side of the hand, a concept explored in depth in Suzuki’s Quint Etudes. This is something that I have been able to experience as a player myself, but haven’t had the words or a method to help a student experience it in the same manner. What began as a small idea to help my student approach their viola more ergonomically has now become a new way of seeing the left hand and a new way of discerning left-hand challenges. The more I explore teaching, I continually find more instances where I can provide students with solutions using this new approach to left-hand set up and balance. I am just as humbled and excited to share these ideas as Dr. Suzuki must have been whenever he shared a “new idea.”

Core Learning

I am lucky to have been exposed to the concepts of Jerome Bruner’s spiral curriculum (Bruner 1960) early on in my teaching development. He describes the content of a learning curriculum as focused on the same core skills and knowledge throughout a learner’s development. As a student gains mastery, what changes is not the content but rather the complexity and application to new contexts. In this model of learning, a student revisits a concept several times throughout their development. With each revisit, the complexity of the topic or theme increases and new learning has a relationship with old learning and is contextualized with old information to facilitate transfer of knowledge. This approach to developing skills mirrors Suzuki’s pedagogical process. When we are able to find a topic’s core and central concepts, it is easy to connect them to many different contexts. The odd thing about when you find one of these core concepts is that it seems to appear everywhere.

Suzuki Violin Teacher Trainer Linda Fiore’s concept of the Three I’s presents another version of this learning model.

Introduction: Skill is taught in a limited context (exercise) or introduced in previous contexts (review).

Incorporation: Skill is applied and performed with focus (one-point learning).

Internalization: Skill becomes natural and automatic with artistic intentionality.

I will borrow Linda’s framework as a way to explore the principles of left-hand balance throughout the res3t of this article. Developing technique on a stringed instrument requires a great deal of different ways to explore our physical world. Motor learning engages our kinesthetic, tactile, proprioceptive, and vestibular senses. Balance is experienced through the equilibrium of suspension and weightedness of tension and release. We experience movement through the center of mass of an object. Exercises allow us to grow in flexibility, strength, endurance, mobility, and range of motion.

Introduction

To find balanced finger patterns, follow the steps outlined below.

Find the center of balance of the hand through strategic and systematically chosen structural fingers.

Align and move thumb–wrist–arm system through motion to experience balance, weight/suspension, and range of motion.

Add remaining fingers, adjusting for accurate intonation and proportions (whole/half steps) for individual hand shapes.

Balanced Hand (Center of Mass) for Finger Patterns

Finger Pattern: 1^2 3 4

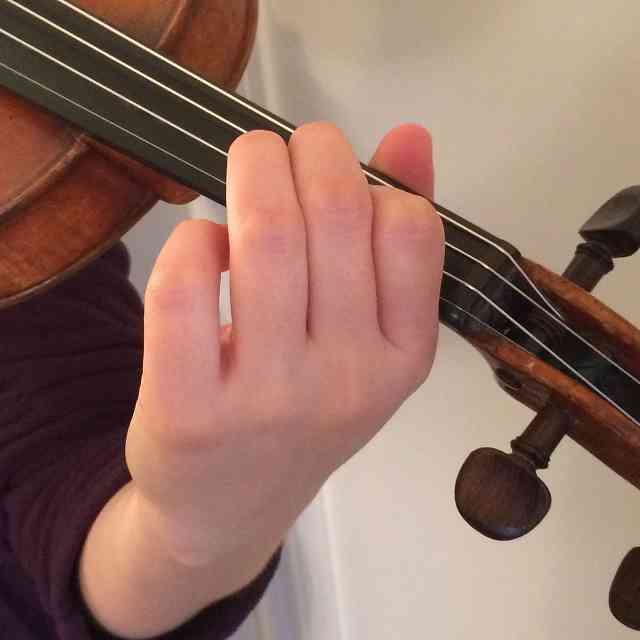

To establish this finger pattern, first plug in a hand frame around the first and third fingers. Wiggle the thumb and align the weight so that it is suspended between the two fingers. Next, tap the fourth finger a whole step above the third. Then, tap the low-two lightly at the tip of the finger, while making sure to avoid twisting out the hand frame. See figure 1.

Finger Pattern: 1 2^3 4

Begin by balancing around the second and third fingers, wiggling the thumb to allow for the hand weight to center over these fingers. Tap the first and fourth fingers individually, in alternation, and simultaneously to find the equal whole-step distance from the central balance around second and third fingers. See figure 2.

Finger Pattern: 1 2 3^4

The second finger is the center of balance in this hand frame. Wiggle the thumb and align the weight over the second finger. Tap the first and third fingers individually, in alternation, and simultaneously to feel the equal whole-step spacing. Then, lightly tap fourth finger a half step above the third, to create a “tuck-in” feeling. Make sure to stay balanced. See figure 3.

Finger Pattern: 1 2 3 4

In this pattern of all whole steps, balance the hand frame around the third finger and wiggle the thumb to align the hand weight. Tap second and fourth fingers individually, in alternation, and simultaneously. Lightly tap the first finger a whole step back from the second. See figure 4.

Incorporation

When you trace this concept through Dr. Suzuki’s volumes of repertoire, it seems like he intuitively or very consciously understood that the hand changes balance with different finger patterns. Looking at Dr. Suzuki’s approach of the 1^2 3 4 finger pattern introduced first in Etude in Book One, we can see that his approach to low second finger is through first setting fingers one and three. Linda Fiore calls this a “plug-in”: place one and three in preparation for placing the low second finger. This allows the low second finger to place without twisting the hand frame and to land on the thumb-side corner. There are instances where the current volumes suggest placing simultaneously. As we introduce this hand frame, following the process of setting the balanced hand allows the center of mass of the hand to shift and allows all of the fingers to proportionally fall to the fingerboard with ease.

Many passages where intonation is challenging are instances where we have to change finger patterns, which therefore requires students to reevaluate and rebalance the center of mass and balance fingers in their hand for fluidity, ease, and accuracy. One example from our repertoire is in the first movement of Bach’s Concerto in A minor, mm. 113–116. The student must rapidly change between three different finger patterns—1^2 3 4 (see fig. 1); 1 2 3^4 (see fig. 3); 1 2^3 4 (see fig. 2)—all in one scalar passage. When teaching this method, we can help students highlight the balance fingers by tapping them, vibrating, and wiggling the thumb.

Double stops require players to have a more complex relationship with hand balance. Often, students leave practice sessions of extended double-stop passages with excessive tension and fatigue. When studying thirds in particular, all fingers need to be placed on the string. When we approach this with the concept of a balanced hand, we place balance fingers first in order for us to feel the center of mass and find the proportional relationships needed to find the whole-half step combinations. In the Marais French Dance No. 2, Provençale, from Viola Book Five, there is an exposed octave in m. 8 that is often out of tune. When we set up this octave with a second finger shift in m. 6, we are actually allowing students to feel the balance finger in the frame 1 2 3^4. When a student maintains this center of mass and balance in their hand, it allows them to have the octave land in tune.

Internalization

As stated earlier, many artist-performers seem to have internalized this concept in their playing, whether it was attained through genius, intuition, or painstaking experimentation and repetition. Hopefully, this foray into thinking about a new way to balance the left hand and explore finger patterns will allow you and your students another way to examine challenging left-hand passages and experience their bodies with more freedom and balance.

References

Barber, Barbara 2008. Fingerboard Geography: An Intonation, Note-reading, Theory, Shifting System. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred.

Bruner, Jerome S. 1960. The Process of Education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Suzuki, Shinichi 1999. Quint Etudes Revised Edition. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred.

Havas, Kató 1981. A New Approach to Violin Playing. Midland, TX: Bosworth & Co.