By Veronique Mathieu

Creativity, or the driving force to effect change, build, develop, and foster growth in the world, is an essential part of human existence. In the realm of musicians, however, this important aspect sometimes gets overshadowed by the focus on mastering an instrument’s technique. Adding to the challenge are the complexities of music itself and the intricacies of notation, often making it seem almost impossible to nurture a student into a truly creative artist.

While there is no shortcut for developing artistry, I have found engaging with contemporary music through graphic scores to be an effective way to unlock students’ creativity. By delving into these visual representations of musical ideas, students are encouraged to explore unconventional paths of expression, fostering a deeper connection with their artistic instincts, and paving the way for imaginative and innovative musical interpretations.

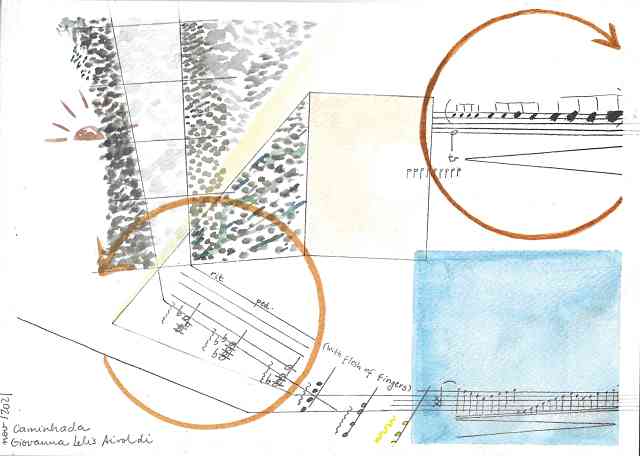

Example 1. Giovanna Lelis Airoldi, Caminhada (2021). This is the entire score. The suggested duration for this work is ca. five minutes. Reprinted with permission.

The Dilemma of Contemporary Music Pedagogy

For centuries, audiences have enjoyed music written by their contemporaries. Composers were often commissioned new works for celebratory occasions, significant events, or for important functions that were relevant at the time of their premieres. However, in the present era, modern composers face a unique challenge. With the remarkable advancements in the printing and recording industries, they find themselves competing with the timeless works of their predecessors for an audience in the concert hall. In the twentieth century, with the rise of modernism and the exploration of new musical techniques, composers embraced dissonances as a means of pushing boundaries and expressing new ideas, often leaving their listeners puzzled. This poses a challenge for performers as well, who are asked to master diverse styles of playing and an array of techniques in order to meet the demands of this expansive repertoire.

Studying the music of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven is the foundation of classical music education and serves as a vital component in the artistic and technical development of musicians. Students learn musical expression, phrasing, and technical precision by studying the core repertoire. Yet, the need and desire for a good understanding of baroque, classical, and romantic idioms generally leave little room in the curriculum for the study of contemporary repertoire.

It can be daunting for a teacher to introduce the notion of microtonality to students when they don’t have full control over their intonation, or to work on different modes of playing when a student is still developing tone production. Meanwhile, there are many benefits to teaching contemporary music to young musicians as it may help develop creativity, critical thinking skills, open-mindedness, and cultural awareness. It not only enriches their overall musical experience but also empowers them to embrace their unique creative voices, complementing the skills they are cultivating through studying the core repertoire.

Graphic Scores

Introducing contemporary concepts through the use of graphic scores is an effective way to familiarize younger students with possibilities beyond classical traditional sounds, without compromising their study of the basic technical elements. Depending on the age or level of the students, teachers can choose to introduce other new and contemporary techniques, giving students the tools to discover an even wider variety of sounds and colors.

Navigating through a graphic score can be a stimulating experience that encourages students to use their imagination, experiment with different sounds and techniques, and explore diverse musical elements such as rhythms, dynamics, and structure in a more intuitive and personal way. It can also create an opportunity to collaborate with others to bring a piece of music to life, or to give confidence to a student who might not be fluent reading notes.

A graphic score (also known as graphic notation or visual score) is a distinctive form of musical notation that uses visual symbols, shapes, and graphics to represent musical elements and instructions to convey a musical idea. Composers may incorporate a brief passage in graphic notation within a larger musical work, or create an entire composition using visual elements. This innovative form of notation has continued to evolve since the mid-twentieth century, opening up an exciting new realm of creative possibilities for both composers and performers.

Several composers have extensively explored graphic notation in their works, pushing the boundaries of traditional music notation. Among them are George Crumb (1929–2022), Brian Eno (b. 1948), and Krzysztof Penderecki (1933–2020), each crafting a distinct and personal notational system for their works. Included are additional examples of scores that feature graphic notation. I selected these pieces because they exemplify how composers have used visual elements to convey their musical visions in unconventional ways, while inviting performers to embark on a journey of exploration and innovation.

Example 1 is Caminhada (Walk), a score created in 2021 by Giovanna Lelis Airoldi, a composition student from the University of Sao Paulo (Brazil), for a collaboration with a group of my students at the University of Saskatchewan. The composer combines standard notation with shapes and colors, giving the performer freedom to interpret the various elements creatively. The suggested duration of this work is around five minutes.

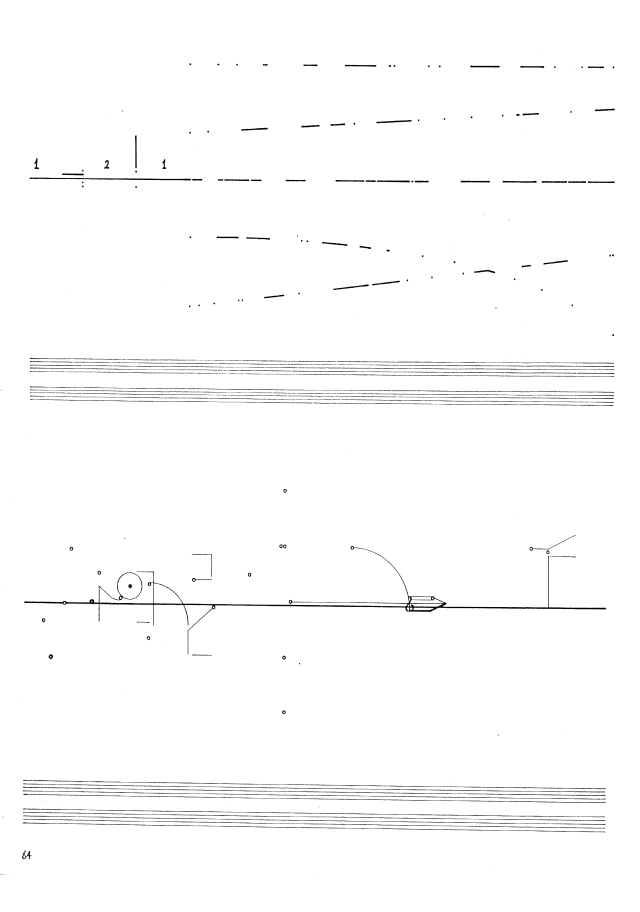

Example 2 is a two-page excerpt from the work Treatise (1963–1967) by British composer Cornelius Cardew. Treatise is a collection of 193 pages of abstract symbols, shapes, and lines devoid of any written instructions for the performers. The graphical elements empower the performers to make individual choices on the interpretation and realization of the music. Cardew intended for his work to encourage performers to engage in improvisation and collective decision-making.

The final excerpt (ex. 3) is the fourth page of a five-page score entitled Dark Night for “any instrument,” written by Canadian composer and improviser Randy Raine-Reusch in 2015. The composer’s instructions are to “perform as if the image an echo, the sound a taste, the feeling a scent, the flavor a touch, the essence a shadow. This piece is performed using sound and/or silence, or by using neither sound nor silence.” Taken together, these three examples show a variety of graphic scores, from an early, seminal example (Cardew), to an established, living composer (Raine-Reusch), to a student composer (Airoldi).

Example 2. Cornelius Cardew, Treatise, pp. 73 and 84.

Introducing Graphic Scores and Extended Techniques

When introducing graphic scores to students, it is helpful to provide guidance and support, explain the symbols or visual elements used, and encourage them to discuss their interpretations. Students can develop their own musical ideas and confidently engage with the creative possibilities presented by the graphic score. Due to the subjective nature of graphic scores, any teacher, regardless of their experience in performing contemporary music, can guide students in interpreting them.

As a starting point, I suggest two scenarios for introducing graphic scores to a chamber music ensemble, or a group of students playing the same instrument. Before engaging with these scenarios, a quick overview of contemporary techniques might be useful. There are several printed resources available for teachers that describe various extended techniques. For instance, orchestration methods like the Essential Dictionary of Orchestration by Dave Black and Tom Gerou provide a comprehensive resource, discussing all instruments. Another useful book is The Contemporary Violin: Extended Performance Techniques by Patricia and Allen Strange, which addresses extended techniques in-depth, and can easily be applied to other string instruments.

Additionally, there are excellent and easily accessible online databases that include musical examples: “The Orchestra: A User’s Manual” by Andrew Hugill, Don Freund’s “Instrument Studies for Eyes and Ears,” Leilehua Lanzilotti’s “Shaken not Stuttered,” and Ellen Fallowfield’s “Cello Map.” Their full citations appear at the end of this article. These resources can greatly enhance the learning experience and understanding of contemporary techniques. It is also important to note that graphic scores can be executed without using any extended techniques, and can be a refreshing way to solidify traditional musical elements such as dynamics and articulations.

Scenario 1

-

Students will collaborate on the interpretation and performance of a graphic score as an interactive group activity. For this exercise, the selected score is Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise, pg. 73 (ex. 2).

-

Six students will be working in groups of two: Group A; Group B; Group C

Before working in pairs, students are invited to identify a list of techniques and ways of playing they wish to consider for their interpretation of the graphic score. Depending on the level and ability of the participants, students can take turns demonstrating the techniques suggested, or write them on a board to later try them as a group, ensuring everyone is comfortable with them. Techniques can include spoken sounds, clapping, pitch repetition, pizzicato, stomping, bowed glissandi, circular bowings, etc. Once enough options have been selected, each group (A, B, and C) will choose a symbol to interpret on the score (dot, short line, long line, numbers), and will experiment with various techniques. At this time, elements such as dynamics, duration, and/or tempo should be considered. After the three groups have had enough time to choose how to interpret their symbols, a first read-through with all players can take place. Students will decide together how to read the score: from left to right, top to bottom, all lines simultaneously, etc. There should be several opportunities to play the score as a group to allow for the students to gain comfort, and to experience the sounds around them.

Example 3. Randy Raine-Reusch, Dark Night (2015), page 4. Reprinted with permission.

Scenario 2

-

Students will contribute independently to the interpretation and performance of the graphic score Dark Night by Randy Raine-Reush.

-

Any number of students

Similar to Scenario 1, students will initially explore different techniques to inspire others to create new sounds. This interpretation will be responsive to the music being played and heard in the surrounding environment. The teacher may provide approximate duration guidelines for the score, offering a framework for the students. Additionally, there can be a brief discussion about where to begin in the score, or alternatively, it can be left open-ended, allowing for greater creative freedom.

Some additional extended techniques can be considered: col legno, tremolo, harmonics, pizzicato, glissando, sul tasto, sul ponticello, vocal effects, scratch tone, circular bow, playing on or behind the bridge. If the students are still working on feeling at ease holding the bow, then favoring techniques that will not compromise their bow hold would be recommended! Other techniques that will not make use of the bow can include tongue clicks, whispers, clapping, or pizzicato. Before attempting to read the score as a group, general parameters can also be identified such as the order of entrances, the amount of time between entrances, a signal to indicate the conclusion of the piece, a general plan for dynamics, etc. Teachers can also choose to play a recording for the students to introduce them to new possibilities prior to working on a graphic score.

Final Thoughts

There are many more graphic scores that are effective in teaching, including Projection 1 for solo cello by Morton Feldman and Music for Airports by Brian Eno. Feldman’s score contains no performance indications, and can easily be transposed for violin, viola, or double bass, while Eno’s score is for open instrumentation.

When working on a graphic score that is more of an artwork representation, students can be assigned a color found in the score, and be given the task of improvising a short passage. When engaging a larger group of students, several smaller groups can be formed, and each group can be given a different page or section of a score to present to the others. Younger students might also enjoy drawing their own graphic scores!

Incorporating an activity pertaining to the study of a graphic score can give some variety to a studio class, provide students with a much-needed break during a stressful time of the year, be a fun way to break the ice at a summer camp or with a new chamber music group, and even be a class project for an outreach event or a studio recital. No matter the occasion you use them for, graphic scores are a great opportunity to foster imagination, open-mindedness, and decision-making.

Extended Technique Resources

Black, Dave and Tom Gerou. Essential Dictionary of Orchestration. Los Angeles: Alfred, 1998.

Fallowfield, Ellen. “Cello Map.” Accessed July 25, 2023. https://cellomap.com/.

Freund, Don. “Instrument Studies for Eyes and Ears.” Accessed July 24, 2023. https://adoring-yonath-076396.netlify.app.

Hugill, Andrew. “The Orchestra: A User’s Manual.” Last modified August 2021. https://andrewhugill.com/OrchestraManual/.

Lanzilotti, Leilehua. “Shaken not stuttered.” Accessed July 25, 2023. http://www.shakennotstuttered.com/.

Strange, Patricia and Allen Strange. The Contemporary Violin: Extended Performance Techniques. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Veronique Mathieu. Photo credit: Julie Isaac Photography

Described as a violinist with “chops to burn, and rock solid musicianship” (The Whole Note, Toronto), Canadian violinist Véronique Mathieu enjoys an exciting career as a soloist, chamber musician, and music educator. An avid contemporary music performer, she has commissioned and premiered numerous works by American, Brazilian, and Canadian composers, and worked with composers such as Pierre Boulez, Heinz Holliger, and Krzysztof Penderecki.

Dr. Mathieu holds the David L. Kaplan Chair in Music at the University of Saskatchewan where she serves as an Associate Professor of Violin. She previously served on the faculty at State University of New York (SUNY) in Buffalo, and the University of Kansas.