By Jenine Brown

Between the original editions from the late 1970s, the revised edition thirty years later, and the international edition, the three editions of the Suzuki violin school method have remained remarkably consistent. That is, the repertoire is incredibly static, with no compositions removed from the books, and only one composition in total has been formally added to the method: Carl Bohm’s Perpetual Motion, from Little Suite No. 6, which was included in Volume Four.

There have been, however, numerous changes to bowings and articulations. A most notable instance is J. S. Bach’s Musette (Suzuki Volume Two, an adaptation of the fifth movement of the English Suite No. 3 for keyboard, BWV 808), which begins on an up bow in the international edition (2020) whereas the original edition (1978) begins on a down bow.1 The impact of the bowing change still has effects today: recently, in a Suzuki group class setting, I observed a student asking questions about why their bowings in Musette were different than those performed by other classmates in the room as they pointed to their score in confusion. Indeed, Cox’s (2011) mimetic hypothesis would explain why I, too, experienced a visceral reaction to the new bowing. Cox’s hypothesis argues that our musical experience includes motor imagery: activation of mirror neurons and muscular activity, even when we are simply remembering or listening to music. I have interacted with Bach’s Musette for over forty years: I am the daughter of a Suzuki violin teacher and I was a Suzuki violin and piano student myself in the 1980s. I have now returned to the repertoire many years later as the mother of a Suzuki violin student, and, likely due to the mimetic hypothesis, I have marveled over my reaction to some of the changes to bowings, articulations, and pitches found in the newer editions. To be clear, my response is not one of a value judgment, it’s simply that my body remembers the composition another way.

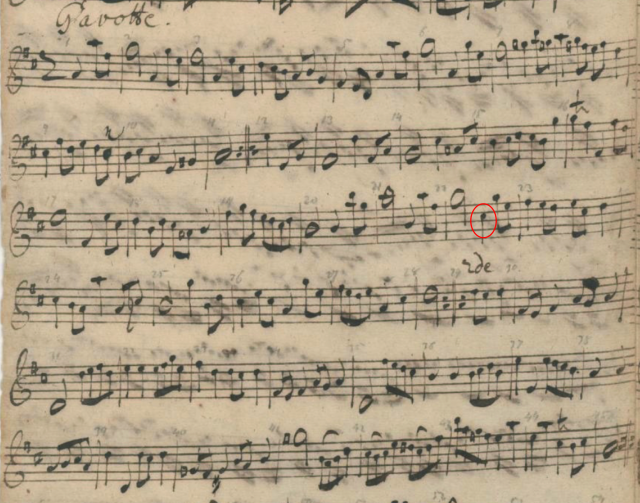

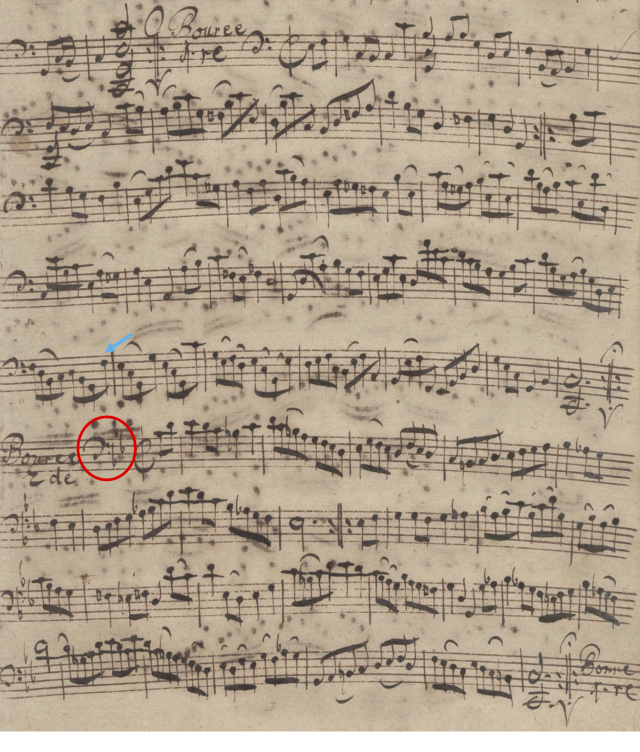

Example 1. The earliest version of the Violin I part from the Gavotte is from ca. 1730 in Bach’s own hand. Note the C-sharp, which I have circled in red (m. 20).

In contrast to the numerous changes in bowing and articulation made among the Suzuki editions, only a few changes to the notes themselves have been made, and the remainder of this article specifically focuses on these. The majority of changes to notes across the editions are to works by J. S. Bach, largely because in the compositions that have been modified, early versions of the works contain these same discrepancies. Kerstin Wartberg alluded to these changes in advance of the release of Suzuki Violin Volume Three, writing that “The Revised Edition of the Violin School Volume Three will come on the market shortly, with alternative versions of the Gavotte I and II and the Bourrée by J. S. Bach” (bolded emphasis in original).2 However, she does not explain the changes that were made, nor a rationale for these modifications. As I am a music theorist by profession, I sought to understand the source of these pitch differences between the original and later editions. Below, I illuminate the various changes to pitch in the two works mentioned by Wartberg and explore why they might have occurred. Through my investigation, I learned more about Bach’s works as they were interpreted, copied, and arranged throughout the last few centuries, and I also gained a deeper knowledge of the history of the Suzuki music school. I share what I learned from that journey herein.

Pitch Changes in J. S. Bach’s Gavotte in D major

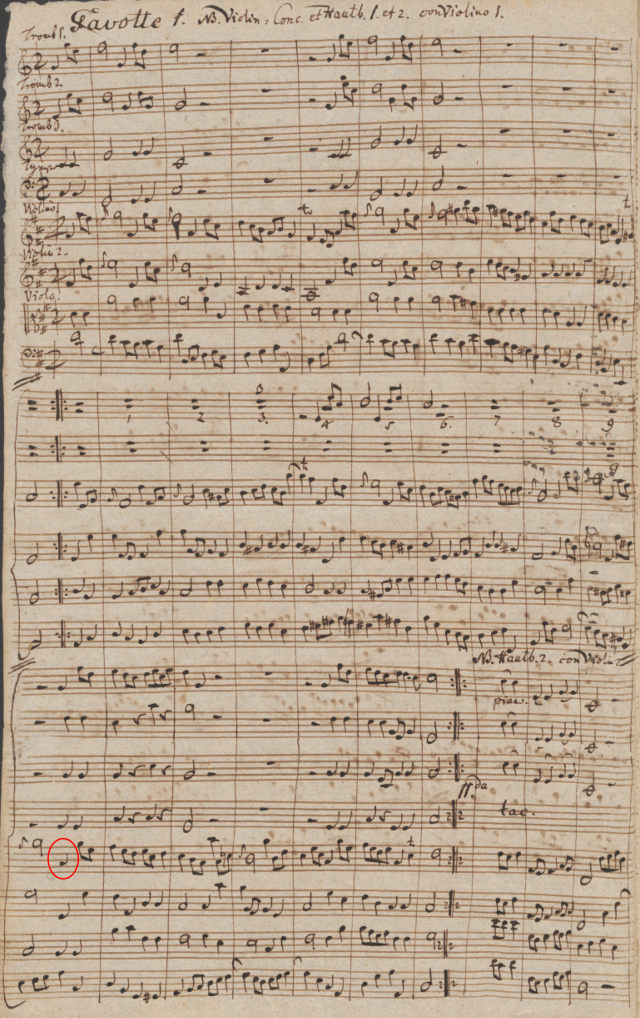

Example 2. The earliest manuscript of the full orchestral score of the Gavotte (ca. 1754) is a copy by Christian Friedrich Penzel (1737–1801). Note the A in the Violin I part, circled in red (m. 20).

In the original Suzuki edition violin part (1978) of J. S. Bach’s Gavotte in D major (Volume Three, #6), measure 20 contains an A4 (scale-degree ^5 in the key of D) halfway through the measure. However, all other Suzuki violin editions, including the earlier 1955 Talent Education Series edition accompaniment score, the original 1978 piano accompaniment (which contrasts with its own 1978 violin part), the revised edition (2008), and also the most recent international edition (2018, 2020), present this note as a C-sharp5 (^7). The viola editions also have these same discrepancies.3 That is, both the 1983 and 1999 viola editions of Volume Three also contain ^5, agreeing with the 1978 violin edition (note that the viola version is transposed to GM as opposed to the violin’s DM), whereas the viola international edition (2018) has ^7 in measure 20.4

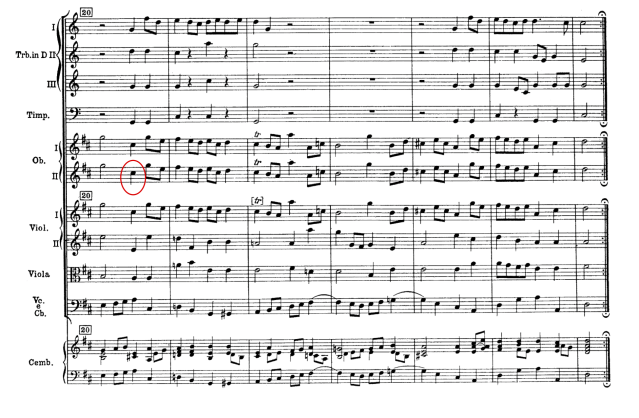

Example 3. More recent editions of the full score contain a C-sharp in measure 20, such as that published by C. F. Peters (ca. 1934).

The source of these pitch discrepancies seems to be that both A and C-sharp can be found in the earliest surviving manuscripts. According to Stowell (1999, p. 336), the first version of this work comes from a manuscript containing just the individual parts, and it is thought that J. S. Bach himself penned the Violin I part.5 Example 1 illustrates this part with measure 20 containing the C-sharp. The full score, however, does not appear until approximately 1754, and is a copy made by Christian Friedrich Penzel (1737–1801). Shown in ex. 2, the source of the A4 seems to be due to this earliest orchestral version. By the time the work appears in the mid-twentieth century, it appears that the C-sharp is accepted as the most correct note (ex. 3), which also agrees with many more recent editions of the work.6 It is likely that the early twentieth-century sources that Suzuki was consulting when selecting the composition for his method would have had not been consistent with respect to this pitch.

Other changes to the Gavotte include that the original manuscripts were composed in cut time (2/2), but the earliest violin (1955 and 1978) and viola (1983 and 1999) editions were written in 4/4. The international editions of both the violin and viola parts restored the original time signature.

J. S. Bach’s Bourrée I and II

Bourrée I and II from J. S. Bach’s Cello Suite No. 3 (Suzuki Violin Volume Three, #7) serves a final example of a work that has changes to pitches between the original to revised editions in the Suzuki Violin School. The following notes were changed over the various editions (note that the international edition restarts measure numbers at “1” at the start of each dance); below, I enumerate these changes:

-

Bourrée I: last note of measure 22 is a D5 in the original edition and is a C5 in the revised and international editions.

-

Bourrée II: third note of measure 2 is an E-flat5 in the original edition and is an E-natural5 in the revised and international editions.

-

Bourrée II: last note of measure 4 is an E-flat5 in the original edition and is an E-natural5 in the revised and international editions.

-

Bourrée II: third note of measure 20 is an E-flat5 in the original edition and is an E-natural5 in revised and international editions.

Example 4. Anna Magdalena Bach’s copy of J. S. Bach’s Bourrée I and II from the Cello Suite No. 3 (copied ca. 1727–1731)

Let us now consider why these notes were changed between the 1978 Suzuki edition and the revised/international editions. Bach’s original manuscript of the Cello Suites is lost, but we might first hypothesize that perhaps the source of these note changes in the Suzuki editions might be due to variations in original manuscripts, similar to what I found in the Gavotte, described above. Scholars often consult four copies of the Cello Suite manuscript, one copied by Anna Magdalena Bach, another by J. Peter Kellner, and two that were copied by unknown authors.7 After consulting these sources, I was surprised to find that the earliest manuscripts of Bach’s Bourrée do not have any differences among the pitches (bowings and ornamentation are another story), and all notes agree with that found in the revised violin edition: for example, see Anna Magdalena Bach’s copy of the Bourrée I and II (ex. 4). That is, aside from differences in bowing and ornamentation (and that the cello version is in the key of C), the notes in the copies from the eighteenth century correspond to that in the revised violin editions.

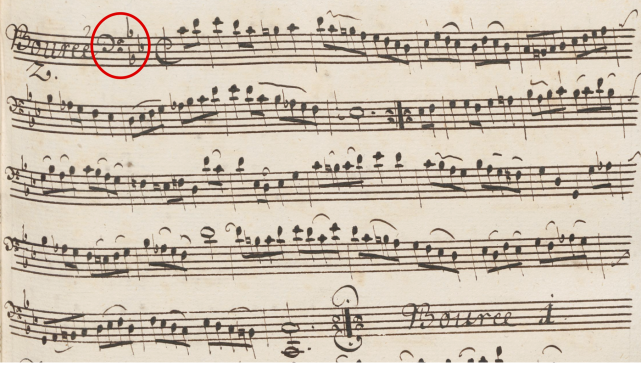

Example 5. The Bourrée II from an anonymous copy (sometimes called the Westphal copy) of J. S. Bach’s Bourrée from the Cello Suite No. 3 (copied ca. second half of the eighteenth century)

Another crucial difference remains. That is, the original Bourrée II in Cello Suite No. 3 starts and ends with a C minor tonality, and a modern composition written in this key would typically employ three flats in the key signature. However, the key signature from the eighteenth-century manuscripts contains two flats (B-flat and E-flat, with a doubled B-flat2 that was customary at the time); I have circled this key signature in red within exs. 4–6. This key signature brings us to the possible source of confusion for changes to pitches numbered #2–#4, listed above, as when the composition arranged for violin and transposed to G, a simple inclusion of an E-flat in a modern G minor key signature of two flats would render these notes different from that found in the eighteenth-century manuscripts.

I think that we could do better as pedagogues to explain that J. S. Bach was writing in a post-modal, yet pre-tonal period in history.8 Indeed, see the entry of “Key Signature” in the New Grove Dictionary: “The association of a signature with a definite key is a late 18th-century development. Before this pieces were often written with, in minor keys, one flat fewer (e.g. Bach’s ‘Dorian’ Toccata and Fugue BWV538)” (bolded emphasis added). For example, there is just one flat in original manuscripts from the eighteenth century for Bach’s Minuet in G minor from the Cello Suite No. 1 and the Violin Sonata in G minor. In the French Suite No. 2 in C minor, Bach uses a two-flat key signature. In contrast, in other works, such as the Cello Suite No. 2 (D minor), all movements contain one flat, so this kind of variation likely confused arrangers and editors in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, leading to the rise of publishing houses in the mid-twentieth century specializing in urtext editions.9 The bulk of this confusion is due to the fact that a composer from Bach’s time could be writing with either a dorian or aeolian (natural minor) key signature, and thus there are often discrepancies as to whether a minor-mode piece should have a raised or lowered ^6.

Example 5. The Bourrée II from an anonymous copy (sometimes called the Westphal copy) of J. S. Bach’s Bourrée from the Cello Suite No. 3 (copied ca. second half of the eighteenth century)

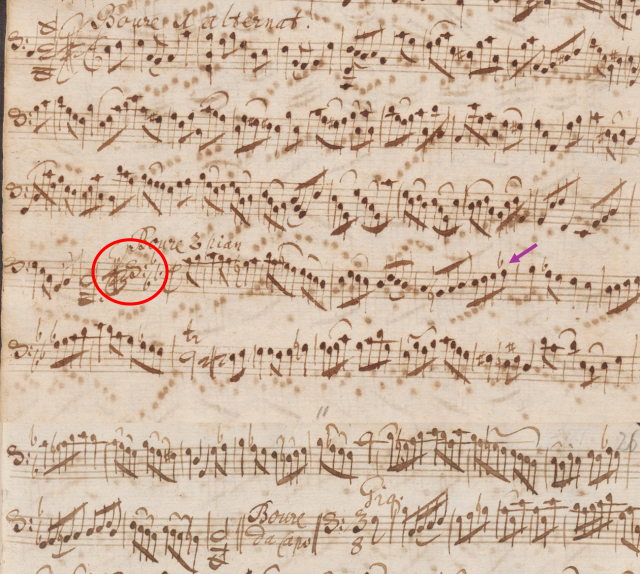

More recent editions of Bach’s works will often use a different key signature––that is, adding one additional flat to works in minor than that found in the original manuscript. In fact, the Bourrée as it is found in the Suzuki violin school seems to derive from Sara Heinze’s (1836–1901) arrangement of the work that was published by Peters in 1872, as her score matches the pitch errors found in the 1955 and 1978 Suzuki violin versions as well as the piano accompaniment, note for note; excerpts from this version can be found in exs. 7 and 8 herein.10 Heinze’s arrangement also utilizes a two-flat G minor key signature, resulting in the augmented second between F-sharp and E-flat in mm. 2 and 20 of the Bourrée that it does not appear that Bach intended. Further evidence that Heinze’s arrangement was the source of that found in the Suzuki editions is that her arrangement calls the work a Loure, as does Suzuki’s 1955 edition. While it is unclear why Heinze calls it a Loure, she may have been consulting the first edition of the Cello Suites, which was published in Paris in 1824, as that publication also calls the work a Loure.11 The composition was renamed to a Bourrée in the 1978 Suzuki edition.

Like the 1978 Suzuki violin edition, Heinze’s arrangement also contains the “wrong note” in measure 22 from the Bourrée I that was changed from a D5 to a C5 in the revised/international edition. The D5 may have simply been a transposition/copy error by Heinze. For example, the correct note (^4) in the eighteenth-century manuscripts is on the fourth line (see blue arrow in ex. 4) but yet remains on that same line in Heinze’s arrangement (blue arrow, ex. 7). Given the different clef (bass to treble) and key (C to G), the note becomes ^5 in Heinze’s arrangement.

Viola and Cello Editions of the Bourrée

The Suzuki viola and cello schools also include the Bourrée and have handled these changed notes in slightly different ways. First, due to the fact that the Suzuki cello program developed somewhat independently from the violin and viola programs (Carey, 1979, pp. 1–2), the Bourrée in the Suzuki Cello School has largely remained the same from that found in eighteenth-century sources, and never underwent any pitch revisions from edition to edition. Yoshio Sato developed the first version of the Suzuki cello repertoire and the Bourrée can be found in Book Five (1972) in the Satō method. The pitches in Sato’s edition agree with all subsequent Suzuki cello editions (the Bourrée is in Volume Seven in Suzuki Cello editions published in 1987, 2003, 2016, 2019), and also agree with the revised/international violin version (with the obvious difference of being transposed in the violin edition). The 2003, 2016, and 2019 cello editions also remove the third flat from C minor key signature found in the 1972 and 1987 cello editions, opting to use the two-flat modal key signature matched by the eighteenth-century manuscripts circled in red within in exs. 4–6 (also corresponding with urtext editions of the Cello Suites).

Example 7. The ending of Bourrée I (mm. 22–28) from Sara Heinze’s 1872 arrangement for violin and piano of J. S. Bach’s Bourrée from the Cello Suite No. 3

The Suzuki viola editions also contain the Bourrée and has its own history of these particular pitches. The first Suzuki viola edition (1983) differs from the 1978 Suzuki violin edition, as Doris Preucil corrected the notes in #1, #2, and #4 from the list above when transposing the violin edition down by perfect fifth, matching the cello editions. Preucil did not, however, change the flat^6 in Bourrée II’s measure 4 up a half step as is found in the revised violin and cello editions, likely due to the fact that the flat^6 is also in the piano accompaniment part (this same accompaniment can be found in Heinze’s arrangement; see the left-hand part in the fourth measure of ex. 8, pointed out with a purple arrow that I’ve added to the score).12 However, recent piano accompaniments have modified their m. 4 of the Bourrée II in the violin and viola international editions, and the violin/viola parts now too contain the natural^6 that measure. Thus, to date, while all violin, viola, and cello parts of the composition may differ on bowings and ornamentation (and the violin version is in G whereas the viola/cello is in C), the notes in the international editions all agree with one another.

Example 8. The beginning of Bourrée II (mm. 1–13) from Sara Heinze’s arrangement for violin and piano of J. S. Bach’s Bourrée from the Cello Suite No. 3

Finally, similar to the Gavotte, the Suzuki editions contain two different time signatures for the Bourrée. That is, the original early eighteenth-century manuscripts of the Bourrée are in cut time, and the Suzuki violin parts themselves from the 1978 original edition and through the international edition also are in cut time. However, all of the violin accompaniment scores are written in 4/4, to include Heinze’s arrangement (1872), Suzuki’s Talent Education Series accompaniment (1955), the original Suzuki violin accompaniment from the 1970s, and even the 2020 International Edition.

Conclusion

This article investigated changes to pitches from original to later editions of the Suzuki violin school, sharing original sources and suggesting why these changes might have occurred. I believe that it is important for pedagogues to embrace these kinds of conversations with our students and share the rationale for the changes that have been made from earlier to later editions of the method. It’s a wonderful way to encourage our students to think about the source of the compositions included in the Suzuki violin repertoire, study original manuscripts, transpose works not originally for the violin, and consider the many uncertainties involved in playing pieces of music three hundred years old.

Notes

1 The original harpsichord score can be found here: https://imslp.org/wiki/English_Suite_No.3_in_G_minor,_BWV_808_(Bach,_Johann_Sebastian)

2 A translation of Wartberg’s full statement can be read here: https://en.germansuzuki.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Bach_for_teachers.pdf

3 The composition is not included in the Suzuki cello and bass schools.

4 This seems to be due to the original violin books being used by Doris Preucil as the source material for the viola school compositions (Oviatt, 2015, pp. 56 and 64).

5 See this website for more information: https://www.bach-digital.de/receive/BachDigitalSource_source_00002507?lang=en

6 All editions cited here can be found at the following website: https://imslp.org/wiki/Orchestral_Suite_No.3_in_D_major%2C_BWV_1068_(Bach%2C_Johann_Sebastian)

7 All of these eighteenth-century copies of the Cello Suites can be found here: https://www.jsbachcellosuites.com/score.html

8 See Lester (1989) for a discussion of this time in relation to mode and key.

9 Still, even urtext editions sometimes modify the original manuscript. That is, whereas both Bach’s original manuscript and Anna Magdalena Bach’s copy of the Violin Sonata No. 1 in G minor, Adagio, have a key signature of one flat and an E4 (natural) on beat 2 of measure 3, the Bärenreiter Verlag Urtext edition adds in an accidental, instructing the violinist to perform an E-flat4 on this note and adding to a continued source of debate as to whether this note should be an E4 or E-flat4. Full scores of Bach’s Violin Sonata No. 1, including Bach’s manuscript, Anna Magdalena Bach’s copy, and urtext editions can be found here: https://imslp.org/wiki/6_Violin_Sonatas_and_Partitas,_BWV_1001-1006_(Bach,_Johann_Sebastian).

10 The full arrangement of Sara Heinze’s arrangement of the Bourrée can be found here (select the “Commercial” tab, and then “Arrangements and Transcriptions”: https://imslp.org/wiki/Cello_Suite_No.3_in_C_major%2C_BWV_1009_(Bach%2C_Johann_Sebastian)

11 This published edition (edited by Louis-Pierre Norblin, published by Janet et Cotelle) can be found at https://vmirror.imslp.org/files/imglnks/usimg/7/7c/IMSLP75797-PMLP04291-Bach_-_Cello_Suites_source_E.pdf

12 There is another possible reason that Preucil left this note as an A-flat, as the Kellner manuscript contains a rogue flat near this note (see the purple arrow pointing this note out in ex. 6). I believe that this “floating” flat applies to the Bb in the measure after it, but one could argue that it applies to the A before it (although the other eighteenth-century manuscripts use an A natural).

References

Carey, Tanya. (1979). A Study of Suzuki Cello Practices as Used by Selected American Cello Teachers [DMA document]. University of Iowa.

Cox, Arnie. (2011). Embodying Music: Principles of the Mimetic Hypothesis. Music Theory Online, 17(2). https://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.2/mto.11.17.2.cox.html

Key Signature. Grove Music Online. Retrieved 5 Jun. 2023, from https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.proxy1.library.jhu.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000014954.

Lester, Joel. (1989). Between Mode and Keys: German Theory 1592–1802. Pendragon Press.

Oviatt, Merietta. (2015). The Preucils: A legacy of music, pedagogy, and the Suzuki viola school [DMA lecture document]. University of Oregon.

Stowell, Robin. (1999). Orchestral suites. In Oxford Composer Companions: J.S. Bach, ed. Malcolm Boyd and John Butt. Oxford University Press.

Wartberg, Kerstin. (2013). Johann Sebastian Bach in the Suzuki Violin School, trans. Mike Hoover. https://en.germansuzuki.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Bach_for_teachers.pdf

Thank you

I am grateful to the following people who have corresponded with me about this project: Meredith Blecha, Tanya Carey, Doris Preucil, and Lisa Sadowski.

Jenine Brown

Jenine Brown (Ph.D. in Music Theory, Eastman School of Music) is Associate Professor of Music Theory at the Peabody Conservatory of the Johns Hopkins University, where she teaches ear-training courses. She suspects that there is a connection between Suzuki’s aural method of familiarization with compositions and why she became fascinated with ear training. Her research is at the intersection of music theory and music cognition, and can be found in Music Theory Spectrum, Music Perception, the Journal of New Music Research, Empirical Musicology Review, and SMT-Pod. Her writings on aural skills pedagogy can be read in the Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy and in Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy. Brown is currently Associate Editor of Music Theory Online and is President of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic. She dedicates this article to her mother and first Suzuki teacher, Linda Lawson. https://peabody.jhu.edu/faculty/jenine-brown/