You have tension. Just relax! Shoulders down. Relax your arm. Play from your back. Stand up straight. Get out of your head! Get into your body.

Perhaps you have heard messages like this on your journey to becoming a better musician. If you were lucky, the teacher or coach provided context and demonstrated clearly, and you imitated them successfully. Or, maybe you tried to follow their suggestion but ended up feeling more confused, unsure if you’d ever get it—whatever “it” was. At worst, you struggled with limitations, developed compensations, or even injured yourself by dutifully applying messages like these to your playing. What about in your own teaching? Do you use instructions like this? If so, when, and what do you notice in your students before and after they receive this kind of information? As a certified Alexander Technique teacher, one of my primary goals is to teach students to release excess tension and move freely, but I completely avoid this type of language. These “relax” messages are unclear and inaccurate because they conflict with how performers need to move and learn. Here, I invite you to think about learning in a more nuanced way and clarify your teaching vocabulary.

As music teachers, we convey an immensely complex process using words, demonstrations, and touch. The music education research literature is filled with studies that organize and explain the characteristics of effective teaching. Novice teachers tend to focus on surface-level problems such as wrong notes, whereas expert teachers thoroughly understand the current and next levels of the student’s development and give meaningful instructions accordingly. Numerous studies of expert teachers have shown patterns of highly organized pedagogical knowledge, rapid decision-making, keen discrimination of detail, and frequent, specific feedback (see, for example, Colprit 2000; Duke 2006; Duke, 2009; Duke & Simmons, 2006; Gholson 1998). This deep knowledge enables great teachers to intuitively choose lesson targets that will bring about the most positive changes for the student. As Duke and Simmons stated, teachers’ “choices of targets are based not only on the achievability of goals, but also on the goals’ contribution to the musical product” (2006, 12). This is why the work of great teachers is so clear, and how they make the complex act of teaching look easy.

Long before these studies existed, Dr. Suzuki named this type of teaching the one-point lesson. Cathy Lee, the Suzuki violin teacher trainer with whom I took most of my units, is a master of the one-point lesson and was also the first person who offered me a truly useful alternative to “relax” messages. “You need both healthy engagement and release,” Cathy emphasized—and then she showed us how! She taught us how to set up a beginner with strong and flexible body balance. Then, she taught us Dr. Suzuki’s whole-arm approach to bowing, which included various bow exercises that activated large muscle groups and movement patterns, as well as many left-hand techniques that were both precise and flexible. I had spent several years in college re-learning my technique and trying to relax while playing. During my teacher training years, I updated my playing yet again. My tone improved, my technique clarified, and I felt prepared to teach my growing roster of students. When we learn to teach, we have the opportunity to re-teach ourselves.

Another way many musicians re-teach themselves is by studying the Alexander Technique, an educational method that helps people consciously improve their thoughts and movements.1 When I teach the Alexander Technique, I find myself describing it in many ways. One of my favorites is this: The Alexander Technique is a way to deliberately take the pressure off of your whole system so that you can do anything with greater ease, clarity, and joy. It is a way to override old habits and replace them with a more efficient way of thinking, moving, and being in the world. A full introduction to the Technique is beyond the scope of this article, and nothing replaces an introductory course in person or online. Instead, I will weave in a few principles that are most relevant to updating your instructional language.

F.M. Alexander (1869–1955) discovered that our head-spine relationship governs the overall quality of our movement, and that we can consciously access and improve these movements. In simpler terms, if your neck is tight, the rest of your body will be more compressed and stiff. You can learn to release pressure from your system by asking your head to move up just a bit, which frees your neck, and allows the rest of your body to follow. Only then will it be possible to move the rest of your joints more freely. Because we move as a whole, trying to release an individual body part while the whole system is compressed will cause compensation and move the tension elsewhere. It is a simple idea, and usually, my Alexander Technique students notice a significant shift in their first lesson. However, integrating this new way of thinking and moving into a highly patterned activity such as playing a musical instrument takes practice. We spend years practicing our technique and creating habits, and it can take time to update those patterns.

When you understand human thought and movement from this holistic perspective, “relax” messages begin to lose their clarity. They are vague instructional targets that offer a surface-level solution to a more complex problem and will not help the performer make meaningful changes. Here are the messages I listed at the beginning of the article, followed by some discussion and new possibilities.

Tension

Old Messages: You have tension. I have tension. You’re so tense! I’m so tense!

I invite you to fundamentally re-frame the idea of tension. Tension is not something you have, or are. Tension is something that you do. Change it from a noun to a verb.

New possibility: You are tightening. I am tightening. By making this crucial shift, you are taking responsibility for what your system is doing. Then, tension is not a mysterious ailment with no cure. If you study the Alexander Technique, you can learn to quickly take pressure off of your system, release tension, and move more fluidly and easily. Even if you don’t take a class, shifting your thinking in this way can be powerful.

“Just Relax!”

Old Message: Just relax! There is nothing wrong with saying this if you’re inviting someone to take a break and rest. However, “just relax” doesn’t fit in an expert teacher’s active instructional vocabulary. You see, music-making is NOT a relaxing activity. The performing arts are a highly coordinated, complex, whole-brain endeavor. We are extreme athletes on a tiny playing field. Musicians can and should cultivate centeredness, clarity, and focus. However, asking someone to relax typically leads to some kind of slump, conscious or unconscious.

Coaching students through performance anxiety is complex and saying “just relax” can feel like a soothing, friendly recommendation. However, it does our students a major disservice. As master Alexander Technique teacher Cathy Madden says, “Asking performers to relax while performing gives them an impossible task. You might as well ask them to be onstage and offstage at the same time” (2014, 74). If you try to relax while performing, you actually pull yourself downward, which causes tightening. From this compressed, incongruent state, your natural adrenaline rush is more likely to spiral into full-blown performance anxiety.

Avoid using the phrase “stage fright,” as it only encourages students to be afraid of performing. Educate parents on this from the beginning of study. Instead, begin talking about performances weeks and months ahead of time. Provide many opportunities to perform before a formal recital, and coach students in stage presence. Ask them to visualize the room full of people for whom they will play. The simple act of acknowledging that they’ll have an audience can be immensely helpful. Let them know that their system will give them some extra energy and adrenaline, which is needed and wanted for an event like a performance. The peak of an adrenaline rush typically lasts for about twenty minutes before calming down, and sometimes, that bit of information can help students cooperate with their biology.

Teens are naturally more self-conscious and are developmentally ready to use principles from the Alexander Technique, so I teach them to take pressure off of their system, then create a performance plan that includes free movement, acknowledgment of the audience, and a plan to send their sound throughout the entire room. This approach requires investment during every lesson for many weeks, but as they practice, the adrenaline rushes adjust and become less overwhelming. These methods have helped even my shyest and most anxious teens perform concerto movements by memory with confidence, projection, and poise!

New possibilities for focused work during lessons: You can move freely while working intently toward a clear goal; mistakes are information. Unfortunately, many people associate diligence and concentration with tightening. And, musicians often tighten in response to errors. It is tempting to tell an overly concerned student to just relax, but remember that this will just cause tightening of a different kind. To create a shift in your studio, try caring for yourself first, because your students will mirror you. The next time you’re in a lesson, pay attention to how you react when a student misses something. Then, observe them carefully. Do either of you narrow, pull down, and tighten? When? When I took the Indiana University music teacher’s workshop, I remember Mimi Zweig saying, “Mistakes are information,” and she invited us to learn from them without harsh judgment. That motto has stayed with me, and helped me bring mindfulness and curiosity to my error-focused work in my own practice and while teaching.

“Relax Your Body”

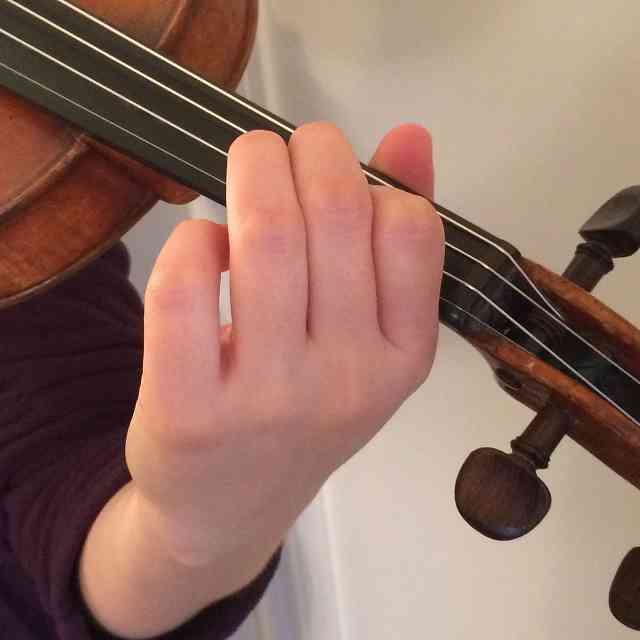

Old message: Put your shoulder(s) down, relax your arm, etc. Instruments like the violin, viola, and flute all involve raising the hands above the clavicle, at which point the clavicle and shoulder area should elevate slightly. “Shoulders down” messages can actually cause injury. Lifting the hands and compressing the arm down at the same time restricts the nerves and blood vessels that run underneath the clavicle. This can sometimes lead to unpleasant injuries like thoracic outlet syndrome, a nerve impingement that causes numbness in the hands.

New possibility: Restore freedom and alignment to the whole body, and then free the whole arm. If a student is tightening their arms, address how their body is moving as a whole first. The Alexander Technique is one of the quickest and most effective ways to do this, but if you don’t have access to a class, here are some simple things to try: walking while playing, walking backward to re-balance through the lumbar spine, standing on a springy foam pad to introduce a bit more movement, standing on one foot while playing to disrupt old patterns, experimenting with pelvic tilt, or doing a deep knee bend and returning to standing in order to reorganize the body.

After you address the whole body, look at the arm. Do you know what a whole arm is, and where it connects to your torso? Many people, even accomplished professional players, will incorrectly point to their shoulder area, where the seam on their sleeve is. Instead, place your hand on the middle of your clavicle (collarbone). This is where the arm connects to the body, at the sternoclavicular joint. Yes, the clavicle is part of the arm! Knowing this will help you move better and teach movement more clearly. For more information, refer to a body mapping book such as Jennifer Johnson’s What Every Violinist Needs to Know about the Body

“Play From Your Back”

Old message: Play from your back. I have heard both string and keyboard teachers use this highly confusing phrase. And, now that I have the highly trained eye of an Alexander Technique teacher, I have seen these teachers actually distort their own movements while demonstrating this concept! When a teacher says “play from your back,” they are likely trying to help the student find greater power and whole-arm coordination. Yes, the arm includes the scapula (shoulder blade) and there are muscles on our backs that work while we use our arms. But “playing from your back” is a terribly unclear way to communicate this, and dutiful students may contort themselves painfully in response.

New possibility: The arms are mostly on the front side of the body, and move in the frontal plane! Send your power into the piano keys, your strings, your bow, etc.

“Stand Up Straight”

Old messages: Stand up straight. This message often results in the student tightening parts of themselves back and down, in an attempt to push the rest of themself up into some idea of better posture. Ouch! Doesn’t that sound like a confusing way to move? Avoid anatomical fiction at all costs. Our spine has four curves. It is designed to be curved. The curves are good.

New possibilities: Stand up curved. Stand tall and easy. Ask your head to move up and the rest of you to follow. The more anatomical truth you bring to your language, the more clearly you and your students will move and think.

The Whole Being

Old message: Get out of your head! Get into your body! People often say this when they notice a performer becoming self-critical, withdrawn, tense, or overly analytical. However, it is not possible to “get out of your head” or “into your body.” We are embodied, whole beings. In his classic work The Use of the Self, F.M. Alexander wrote that “it is impossible to separate ‘mental’ and ‘physical’ processes in any form of human activity.” Today, the fast-growing field of neuroscience is explaining the mechanisms of mind-body unity. For a fun, accessible story on this topic, look up Jon Hamilton’s NPR story entitled “An Overlooked Brain System Helps you Grab a Coffee — and Plan your Next Cup.” 2

New possibility: Think whole. The Alexander Technique taught me that we are whole beings and that movement is embodied thought. The thoughts and words we use become embedded in our movements. Performers need to move with clarity, energy, efficiency, and poise—not to relax. With your larger knowledge base and a more precise teaching vocabulary, you’ll choose more effective goals for your students, and they will reap the rewards. So, instead of “relax,” choose ease, clarity, and joy!

Notes

1 For a more detailed story about the role the Alexander Technique has played in my life, log into your SAA account to read my article in ASJ Vol. 52, no. 1: https://suzukiassociation.org/news/navigating-wilderness-overuse-injury-with/

2https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/04/20/1171004199/an-overlooked-brain-system-helps-you-grab-a-coffee-and-plan-your-next-cup.

References

Alexander, Frederick Matthias. 2001. The Use of the Self. London: Orion Publishing.

Colprit, E. 2001. “Observation and Analysis of Suzuki String Teaching.” Journal of Research in Music Education, 48(3): 206-221.

Duke, R. 2006. “Beautiful Teaching” The American Music Teacher, 56(2): 22-24.

Duke, R. 2009. Intelligent Music Teaching: Essays on the Core Principles of Effective Music Instruction. Austin, TX: Learning and Behavior Resources.

Duke, R. & Simmons, A. 2006. “The Nature of Expertise: Narrative Descriptions of 19 Common Elements Observed in the Lessons of Three Renowned Artist-Teachers.” Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 170: 7-19.

Gholson, S. 1998. “Proximal Positioning: A Strategy of Practice in Violin Pedagogy.” Journal of Research in Music Education, 46(4): 535-545.

Johnson, Jennifer. 2009. What Every Violinist Needs to Know About the Body. Chicago: GIA Publications.

Madden, C. 2014. Onstage Synergy: Integrative Alexander Technique Practice for Performing Artists. Chicago, IL: Intellect.