Have you ever imagined that given the opportunity, you would sit in an auditorium in a foreign country, for perhaps ten hours a day, listening to young musicians play compositions by only one composer, sometimes the same composition repeatedly?

This was the environment in which I found myself in October 2010, when I attended the Fryderyk Chopin International Competition in Warsaw, Poland. Before I was there, I imagined getting tired, bored, and antsy as the days unfolded. That never happened. Even on the day I arrived, having traveled overnight from the US, I was wide awake and stimulated beyond my expectations. When that session ended at ten in the evening, I could hardly sleep from the excitement! The next morning, I could not wait to get back to the auditorium for more performances.

This particular competition takes place once every five years. The 2010 event was the sixteenth time it was held, and because of the 200th anniversary of Chopin’s birth, the competition took on a greater significance than usual. Eighty-one pianists from twenty-two countries performed and vied for the prizes. They were between seventeen and thirty years old, and many of them were already young artists of the highest caliber. Most of the participants had traveled to Warsaw the previous April for the Preliminary Round of the competition, in which 346 pianists had performed.

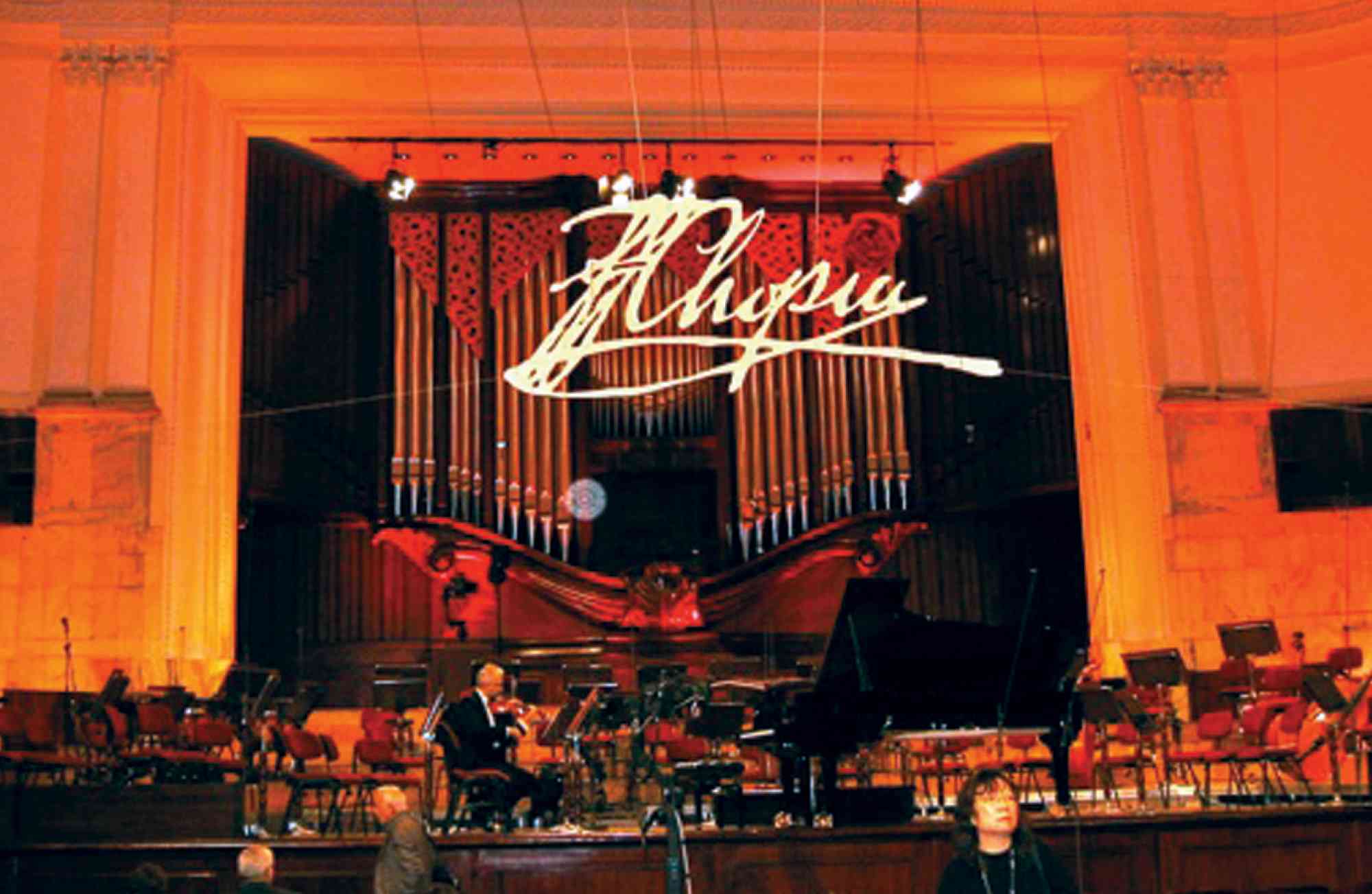

The Chopin Competition is divided into four rounds, not including the preliminary round, and all were held at the National Philharmonic Concert Hall. There are very specific requirements for each round. For example, in the first round, most of the candidates played two etudes, one nocturne, and then either a ballade or a scherzo. They chose their selections from a specific list of repertoire. As many as sixteen pianists would play on one day, and each program lasted around twenty-five minutes. At the end of that round, forty-one participants were eliminated. During the second round, with forty contestants remaining, the individual programs became longer and included ballades, scherzi, waltzes, polonaises, and preludes, once again of the performer’s choice from a specified list. After all of the performances, twenty more candidates were eliminated.

I was not present for these first two rounds, but I was able to watch many of them online via the official competition website. Each performance was streamed live over the internet and saved so that one can watch them when convenient. One could do repeated listening of each performance, as well as recommend particular performances to students and colleagues. Before I traveled to Warsaw, I had already chosen a few of my favorite participants. I also knew one of the contestants personally as a Suzuki trainee! Two others had studied in Philadelphia, and I had heard good things about them. It was exciting to have even a small connection to these young pianists.

I arrived on the first day of the third round, for which there were twenty candidates. I heard sixteen of them. Each was required to perform the Polonaise-Fantasie in A-flat Major, Op. 61. They were also required to perform one of Chopin’s three piano sonatas, all of which are gigantic works. Following that, each contestant performed additional works of their choice, such as impromptus, nocturnes, preludes, and fantasies. These programs lasted about one hour each. Performances would begin at 10 a.m. and last until 3 p.m., with a thirty-minute break around noon. There would then be a two hour break, during which most people would eat a meal. I remember sitting at one restaurant and hearing many people at tables around me discussing the performances and choosing their favorites. We were all back in the auditorium by 5 p.m. for the next set of performances, which continued until 10 p.m.

The Chopin Museum in Warsaw, Poland

In the third round, I heard sixteen performances of the required Polonaise-Fantasie. I also heard eight performances of the Sonata in B Minor and eight performances of the Sonata in B-flat Minor. Each one was different from the previous one. Even though I had been familiar with this repertoire, I was surprised at my own ability to notice small nuances of tone color, phrasing, tempi, and other musical aspects. At the end of each performance, I found myself eagerly waiting for the next one! I kept thinking how fortunate I was to be sitting there as such beautiful music washed over me. The acoustics in the hall were wonderful. Never before had I taken the time to listen to Chopin’s music played by many different artists. It was truly revelatory to me, and I felt as if l was experiencing the art of listening on a higher level than ever before.

There were four different pianos available for the competition, and the contestants could choose the piano they preferred. All of the pianos, including a Steinway, a Yamaha, a Kawai, and a Fazioli, were on stage. Between performances, a crew would move the chosen piano into place for the next contestant. This, of course, added yet another element to the listening experience. The pianos were different in sound quality from each other, but two different pianists could even make the same piano sound quite different.

The audience was made up of people from all over the world. During breaks, one could hear languages from different countries all at once. At times, I felt I was in Tokyo because of all the Japanese being spoken. It made quite an impression on me that although the Japanese contestants had been eliminated by the fourth round, the large number of Japanese audience members stayed for the final concerts. Michie Koyama, a member of the jury who had won Fourth Prize at the competition in 1985, was quoted as saying,

Japan is called the Land of the Cherry Blossom. These trees bloom in Japan for a week with translucent, delicately pink flowers. It is the embodiment of ethereal beauty and perfection of nature. Just like Chopin’s music. We love him for gentleness and elegance, but also for that which is hidden deeper, the emotional essence to which you have to break through, just like to the soul of the Japanese.1

There were lots of Poles in attendance, of course, who take great pride in this event. They followed their own Polish contestants as if they were young aspiring athletes or rock stars! At times, there were groups of Polish school children in the audience, already learning to appreciate one of their national heroes. I recently came across an interview with Piotr Anderszewski, a Polish concert pianist who lives in Paris. He was asked if music had been played in his household as a child in Warsaw. He answered, “My biggest memory is of the Chopin competition, which in Poland is bigger than football. I remember my aunts and great-aunts arguing about who played the mazurkas better in 1956. They got so angry they wouldn’t speak for days.”2

For the fourth round, ten pianists were selected to compete for the final prizes. This was the Concerto round, and each performer was required to play one of Chopin’s two piano concerti. The Warsaw Philharmonic, conducted by Antoni Wit, was on stage to accompany the performers. Eight of the pianists chose to play the Concerto in e minor, and the other two chose the Concerto in f minor. Because of the difficulty of obtaining tickets to these programs, I was only able to hear four of the contestants play concerti.

By this round, everyone in the audience had made their choice of who they thought should win this competition. There were clearly audience favorites, who often received bigger ovations than some of the other contestants. The performances ended at 10 p.m., and it was difficult to leave the auditorium while wondering when the judges would announce their results. By morning, everyone knew who the winners were, and we could all rejoice, express our surprise, disagree, or perhaps just accept what was now final.

There were twelve judges. They included Martha Argerich, Dang Thai Son, Bella Davidovich, Philippe Entremont, Fou Ts’ong, Nelson Freire, Adam Harasiewicz, Andrzej Jasinski, Kevin Kenner, Michie Koyama, Piotr Paleczny, and Katarzyna Popowa-Zydron. Many of them had been prize winners in past competitions, and they have all had illustrious musical careers. They used a complicated rating system when voting after each round of performances. They were highly respected, of course, and were seated each day in the first row of the balcony. Their presence added to the excitement of each performance. Audience members were left to wonder just what special spark or musical initiative the judges were listening for.

Chopin’s gear in the Church of the Holy Cross

Yet to come was the First Winners’ Concert, where each winner performed once again and then received his or her prize. This was a very big event in Warsaw’s musical circles, held at the Polish National Opera Theater. The audience came dressed in fancy gowns and tuxedos. Important government and cultural officials made speeches. There were six prizes in all, which included two second prizes. Separate awards were also given for the best performance of a polonaise, of mazurkas, of a concerto, of a sonata, and of the Polonaise-Fantasie in A-flat Major, Op. 61. The Gold Medal winner, Yulianna Avdeeva from Russia, once again performed the Concerto in e minor with the Warsaw Philharmonic. She was the first woman to be awarded the first prize since Martha Argerich in 1965.

There was also a Second Winners’ Concert and a Third Winners’ Concert on the following consecutive nights. The winners played different Chopin selections on those concerts. Each of these concerts was sold out. The Polish people and the world were celebrating the accomplishments of a new group of Chopin artists.

The entire competition, from beginning to end, was available not only online but on Polish National Television as well. There were commentators, as in a sporting event, who would do interviews or banter about the performers during intermissions. The population of Poland clearly identifies with Frédéric Chopin: the man, his music, and his legacy. In addition to the television coverage, there was a daily newsletter called the Chopin Express that was printed every night after that day’s performances and then passed out the next day on street corners throughout parts of Warsaw. These newsletters were each eight pages long and included reviews by various renowned music critics as well as interviews of the judges and articles about the history of Chopin or the competition. There were also beautiful photographs of the contestants, the judges, and scenes of the competition. Every article was printed in both Polish and English. Twenty-one issues were published in all, and at the First Winners’ Concert, a beautifully bound notebook including all of the issues was given to each audience member. Each day of the competition, CDs were released featuring a selection of performances that had taken place up to that point. Once again, these CDs were free and passed out on the streets.

Not long before the competition began, a new museum dedicated to Chopin opened in Warsaw. It is in a beautifully restored building and features lots of interactive exhibits. It is another place where one might find large groups of school children. Across from the museum is the Chopin Store. Many books and CDs were available, some of which had been published especially for this sixteenth competition. Of special note is The National Edition of the Works of Fryderyk Chopin, edited by Jan Ekier, and just completed in 2010. For the Poles, this edition is now the authority on the interpretation of Chopin. There were also CDs of Chopin’s works recorded on pianos like the ones that Chopin himself played on, namely a Pleyel piano and an Erard piano.

On October 17 each year, a special concert featuring the Mozart Requiem commemorates the anniversary of Chopin’s death. It is held at the Church of the Holy Cross, where Chopin’s own heart is buried. Last year, when I was there, I was able to hear a repeat performance the following night in an intimate setting at the opera house. The musicians performed this work on period instruments, which was very strange to me, but I consider it to be one of the most interesting and memorable concerts I have ever heard.

Joan (right) and Eva Guz-Seroka, a piano teacher trainer in Warsaw, having tea at the Chopin University where Eva teaches

During my visit, I was also able to make a personal connection to the Suzuki community in Warsaw. There happen to be two European Suzuki Association Piano Teacher Trainers living there, both of whom speak English and were able to meet me for afternoon tea on separate occasions. One of them does some teaching at the Fryderyk Chopin University of Music, formerly the Fryderyk Chopin Music Academy, and so she gave me a tour of the building and showed me where the competition pianists were able to practice. The other Suzuki teacher was quite proud of one of the contestants, who had been her student when he was a young boy.

During the months since I have been in Warsaw, I have found other occasions to listen to particular repertoire numerous times by different artists, both by myself and with other teachers. What an experience! When listening to numerous performances with others, we often do not agree! But we do enjoy discussing the performances and what we like or don’t like about them, and that is very stimulating. I have also included more listening activities like this in my own studio, both at individual lessons and in group lessons. And, of course, I have spent more time studying YouTube performances to recommend to my students.

This was an experience that I shared with my husband, a Polish-American who feels a strong connection with his Polish heritage. He had been to Warsaw on several occasions, but this time he, too, was overwhelmed by the magnitude of this extraordinary cultural event. We are already talking about returning in 2015!

Notes

- Roza Swiatczynska, “Climate for Chopin: an interview with Michie Koyama,” Chopin Express 18, October 2010, 4. ↩

-

Hewett, Ivan, “Interview with Piotr Anderszewski,” The Telegraph, May 20, 2009

↩