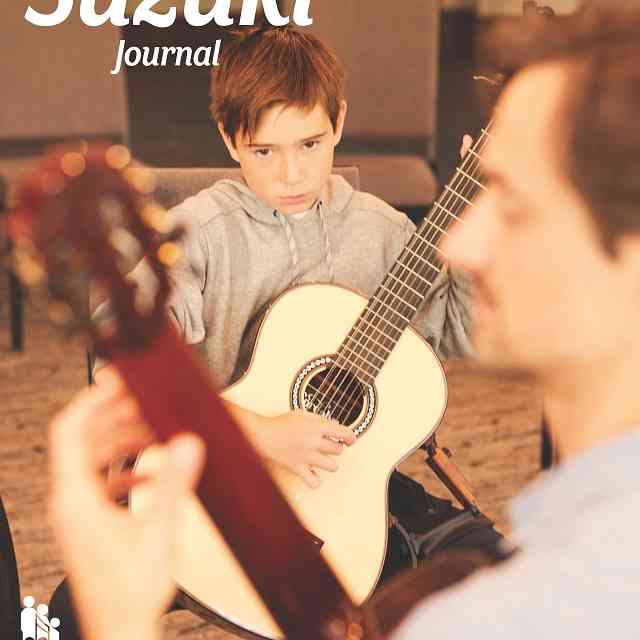

Montessori student

As a Suzuki teacher, I often hear of the similarities between the Suzuki Method and Montessori education. I wondered about it myself until September 2009, when I became an assistant teacher at the Marquette Montessori Academy. I experienced the method—specifically, the preschool level, where I teach—first-hand, and gained insight into these similarities in philosophy.

The Montessori preschool classroom is an extremely organized space lined by shelves for each of the five curriculum areas: practical life, cultural, sensorial, mathematics and language. On the shelves are trays full of objects which teachers call “materials,” arranged in sequential order, increasing in difficulty and organized top to bottom, left to right. Teachers place each material to teach a specific lesson, and the materials are designed to be attractive to children and hold their interest. Children are welcome to work with any material as long as they know how to use it. As children master them, materials are changed. New materials are often an extension of the previous, requiring increasing knowledge or skills. Similarly, the Suzuki Method uses carefully chosen sets of books in sequential order. Each piece has built-in teaching points and attracts children’s attention and interest.

Montessori teachers are very careful in choosing the materials placed on the shelves because they know that children learn from their environment. For example, if the children need to practice fine motor skills, such as the use of their thumb and pointer finger, a Montessori teacher might put out a tray of tweezers and toothpicks or a scoop with a dish of rice or beans. Furthermore, children will emulate their teachers’ behavior—if teachers see the children need to learn to use quiet voices, they will make sure to use quiet voices themselves. Dr. Suzuki recognized that children learn from their surroundings. If children have a musical environment, music will be second nature to them. Suzuki teachers encourage parents to provide many musical opportunities for their children. Parents are asked to play the accompanying CD of the Suzuki repertoire as much as possible, and even parents without musical training can provide an enriching musical environment in this manner.

Montessori student with lead teacher Lisa Vukmirovich building pink tower blocks

At the start of the day, the children are welcomed to enter the Montessori classroom in a calm and orderly manner with quiet music playing the background. They are encouraged to find works of their choice. A younger child may choose to work on the pink tower, which is a set of ten blocks in decreasing sizes, stacked up from the largest to the smallest. The teacher demonstrates, and then the child is allowed to work alone. The teacher observes the child’s work, but will not interfere unless the child is being destructive or asks for help. The child is to recall the lesson given or figure it out by experimenting and trying over and over again.

Many Montessori materials are self-correcting. If the child makes a mistake, the pink tower will not look right. Similarly, Suzuki students are encouraged to play by ear, figuring the notes to the songs by trial and error after they have heard them multiple times on the CD. A Suzuki teacher can help in this process, but will try to refrain from showing them every note, instead asking questions such as, “Do the notes you just played sound like the song we hear on the CD?” and “Can you help me sing the song and then find those notes?” The point of reference is what the child hears versus what he or she produces on the instrument. The child is to self-correct with the teacher’s prompting and encouragement.

Montessori teachers are constantly circulating, directing, monitoring and giving mini lessons to an individual or a small group of students. There are two teachers in each classroom: a lead teacher and an assistant. A lesson is called a “presentation.” When giving a presentation, the teacher invites children to bring material to a rug or a table and proceeds to teach in a calm and quiet manner, often using the three-period lesson format. The three-period lesson uses the statements “this is,” “which is?” and “what is?”

Montessori student with Wee Ling Sim, working on the sounds of the alphabet

If the lesson is to learn the sounds of the letters of the alphabet, the teacher will show by saying the sound of a while tracing the sandpaper letter (letters cut from fine grit sandpaper and mounted on cards are used in Montessori classrooms to create a tactile experience with each letter), and then the child repeats. Then, the teacher asks which letter is the letter a, and the child must point to the correct letter. Finally, the teacher points to the a and asks the child, “What is this?” and waits for the child to respond verbally. If the student is unable to choose the right answer, the teacher does not correct, but assumes the concept of sounds is not learned. The teacher can then go back to the previous step or teach the lesson again on another day until the student has mastered it. Much care is taken to ensure each step is learned before proceeding to the next. This is similar to the teaching by demonstration and imitation, teaching in small steps, and the constant review of learned materials for musical refinement that are used by Suzuki teachers.

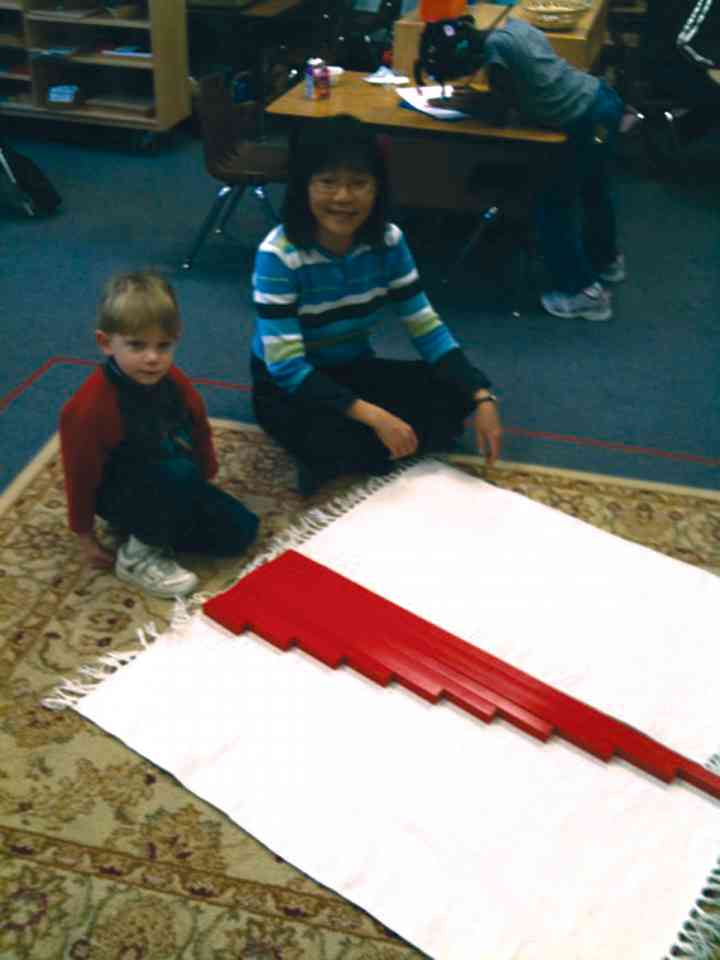

Placing red rods in order of length

Placing red rods in order of length

Montessori students are on the move while learning. Founder Dr. Maria Montessori believed movement is cognition in a young child. The red rods lesson from the sensorial center requires the child to select from the shelf ten wooden rods of increasing lengths one at a time, while stretching the arms to hold the ends of the rods (which teaches the child a sense of length), set them on the rug, and arrange them in the correct order from the longest to the shortest. This might seem tedious to an adult, but not so for the child. The repetitiveness of the work is a purposeful use of movement while thinking. Using the red rods, the child learns longer versus shorter by touching, holding and feeling.

Children are urged to work on a lesson repeatedly in the Montessori class. Frequently, children want to do a lesson often, as it is interesting and enjoyable to them. Repetition is a necessary part of learning an instrument. As a Suzuki teacher, I try to find ways to encourage repetition in a positive and enriching way. I might play a game of tic-tac-toe with a child when I need him to repeat a measure or give away beads for each correct playing. I believe both Montessori and Suzuki teachers understand that the mastery and fluency of a skill is achieved through sufficient repetition.

The language shelves of the Montessori classroom are full of objects to match sounds and pictures to words. Montessori teachers teach the sound of the letter before the name of the letter. For example, instead of saying to the child “This is the letter a,” we say, “This letter has the sound ai” while we trace the letter. As described in the three-period lesson, the child is to copy the teacher. Next, the teacher asks the child to point out the letters and then ask him to name the sounds of the letters.

The child might progress to working on objects and the beginning sounds. He would pick out a small doll from a sound basket, say “doll,” and place it under the d card. A drum, a dog, a pin, a table, a pie, and a tool might be in the basket, and the child will have to sort these objects according to the starting sounds. The objects are copies of real life models. The idea is children must touch, feel, and experience firsthand. Later, they will progress to matching pictures of the objects with the words. Concrete concepts in the form of objects always come before abstract ideas. Students might line up beads while counting or match cards while practicing rhyming words. Movement is an intrinsic part of learning, as in the Suzuki Method, where a teacher tends to delay the reading of music until the tone production, body posture, playing position, and listening skills are well established.

There are three different age groups of students in a Montessori classroom. The preschool level consists of three-, four-, and five-year-olds. It is believed children learn effectively through observation and imitation, especially of their peers. The natural tendency of all children to copy others is utilized and encouraged by the Montessori method. The mix of different age groups also serves as an inspiration for children to try out new and harder materials. I have often observed a three- or four-year-old child wanting to try out a work after watching an older child’s lesson and then asking the teacher for a presentation or figuring it out for themselves by remembering what they saw.

The benefits are also tremendous for the older children. They take on leadership roles of teaching lessons they’ve already mastered, thus reviewing their previously learned materials. The older students become role models, showing younger students the social and caring aspects of a Montessori environment such as how to walk and talk in hallways, how to interact in an acceptable way during snack time, how to share, how to take care of conflict if it arises, and how to help others whenever needed. The Suzuki Method incorporates the individual lessons and group classes, as well. This serves as a motivational, inspirational, and fun experience for the children while they play and perform together. Dr. Suzuki taught his individual lessons in the form of master classes, where students observed one another. He knew children learn by watching and are motivated by their peers. Seeing others’ accomplishments helps children realize that they are also capable of such ability.

Of course, there is more to Montessori education than what I have described, but these similarities in Montessori and Suzuki philosophy are the most striking. I have been very lucky to be present in a wonderful environment of children on a daily basis. What better way for me to learn than through observation and practicing the theory hands-on? I have been able to draw upon my Montessori experience and incorporate aspects of it in Suzuki teaching, and vice versa. It is my hope that others benefit as I have from my observations and insights of Montessori and the Suzuki Method.