We asked some Suzuki trailblazers to reflect on what impact the method had on music education in the last 50 years and how the method has developed. We are grateful for the role so many community members had in making the SAA what it is today. Read on to learn more about the part some early SAA leaders played in bringing the Suzuki method to America and shaping our organization.

Early sparks that lit the flame

“My dad, Sandy Reuning, was one of the pioneers of the Suzuki movement in the United States. He was one of the younger members of the original board of directors and is still doing great at the age of 87. It was an honor to collaborate with him on this piece.

I was 14 when the SAA was established, and many memories are still vivid. But it is the feeling of that time that lingers to this day. Through my own memory of those impressions, I will start by setting the stage leading up to the formation of the SAA. The second part of this piece will be an interview with my dad, talking about some details of how the SAA began. I will conclude with my own thoughts about how fortunate we are as an organization to benefit from the foresight of our early leaders.

Imagine that you are a young child knowing that tomorrow is your birthday and you will be having a party and receiving presents from loving guests. Can you feel it? That was the underlying feeling of excitement that we had in our home beginning in 1964 when my parents, who were both violinists and teachers, heard the first Japanese tour group in Philadelphia. Once they heard the opening of the Eccles Sonata, they were hooked. My parents knew they had to become teachers of the Suzuki Method after hearing the children produce such a beautiful, rich, and full sound on their violins. They just needed to find out how. This same spark was lit around the United States and Canada.

All four of my siblings started playing as well, so it became a full family affair. Shinichi Suzuki was generous with his time and energy, visiting, again and again, to help teachers learn a radically different way to teach. Whenever he was anywhere near us in the region of upstate New York, we would travel there and take part in the demonstration lessons. Our family also traveled widely to share Dr. Suzuki’s ideas with other teachers.

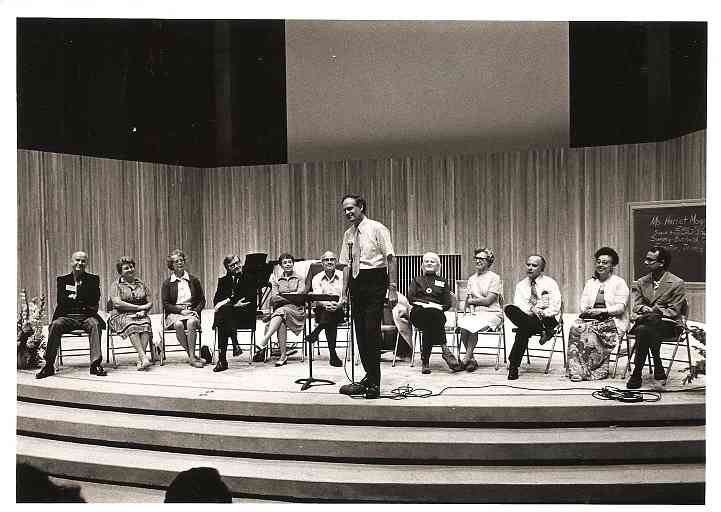

In the summer of 1971, Margery Aber formed the American Suzuki Institute in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, modeled after Suzuki’s Japanese summer school. My dad was invited to teach there, and I went along to participate as a student. Upon arrival, the excitement that I had felt through my childhood was bumped up—as if on steroids! Everyone was learning and growing. The kids were having the time of our lives in the dorms, heading to the cafeteria, walking to classes together, and playing violin all the time. The teachers were having the same experience of hanging out with each other until all hours of the night. The recitals in Michelson Hall were particularly exciting. We could all fit there at once back then. Teachers would be inspired by the students who played, which would give another chance for late-night talks about pedagogy.

Now let’s hear from Sandy Reuning about his memories of the birth of the SAA.

Tell me about those first couple of years in Stevens Point.

At the end of the first year, we had a meeting with all the teachers who were observing. A gentleman stood up and said, “I have a question. What is this I keep hearing about listening to a recording?” It was evident that there were so many things missing or misinterpreted. Training teachers became a central thing that needed to be addressed.

Stevens Point became very important as a meeting place for teachers because we were at the point in our development in the U.S. where it was time to begin and organize our own training. Before this time it was more difficult to meet, although there were some key opportunities here and there, such as Project Super in Rochester, New York, (1966) which brought teachers together from each state by scholarship.

How did the early leaders decide on the need for an organization like the SAA?

It was apparent that we needed a forum for things like a journal to disseminate ideas. It was equally important that we would have an answer to the question, “What is a Suzuki teacher?” We needed to know that “I am a Suzuki teacher because I have this training. I am not a Suzuki teacher because I don’t have this training.” We wanted to codify that so that people were not setting up shop as Suzuki teachers after a day or two of training.

What was the first order of business at the meetings in Stevens Point?

We set up procedures for democratically-run meetings. It was important to find our leaders right away, which was not difficult thanks to the involvement of John Kendall, Bill Starr, and Louise Behrend. The big thing was really to get training going. Out of necessity, we appointed ourselves as the first trainers. We also needed to figure out how to do the training. Up until this point, most of the training was not so systematic, and teachers would tackle multiple books at a time.

There were several camps of belief about how the training should be set up: a certification system modeled after Dalcroze Education, having a Suzuki Center, or opening the whole thing up so that anyone could call themselves a Suzuki teacher. We settled on a middle ground where someone must receive training in Book One before they could call themselves a Suzuki teacher. We wanted to encourage people to come in, not keep them out. We knew this decision was just a starting point.

Tell me about the first presidents.

The first president was Bill Starr. He had spent a whole school year in Japan with his family, including his wife, Connie, who was a Suzuki piano teacher. This experience gave him an important relationship with Dr. Suzuki. Both Bill and Connie wrote essential books, particularly Bill’s The Suzuki Violinist. The second president was John Kendall, who visited Japan initially, wrote slightly revised Suzuki books, and traveled all over the world sharing Suzuki’s ideas. I was the third president. The publishing company of our Suzuki books, Summy Birchard, provided us with an executive secretary to get us going for the first several years.

What helped you all stay connected and keep a forward motion?

The SAA published the American Suzuki Journal, printed materials, spearheaded the development of books and recordings, developed repertoire for instruments, hosted national and international conferences, and on and on! The Stevens Point hub continued to be key, and many more institutes sprang up after that—first in Ithaca and Ottawa, Kansas, then all over. The SAA began to oversee these new institutes to retain the quality of the teaching and training. It was so vital that more and more of us could keep talking and learning and developing our skills as teachers and trainers, and we needed to retain the quality.

How did you keep the energy to make all of this happen?

The excitement kept us in motion. We saw what our students needed and just kept the next things happening.

Thanks so much for sharing this information with us!

I have been thinking a lot about how phenomenal it was that this grassroots effort took off so fully. There were a number of very important factors that lined up to make up this possible and if any one were removed, we would have very different results.

-

Shinichi Suzuki was so generous with his travels here, his energy, and his sharing of ideas. He had a trust in the teachers, just as he had with the children. Suzuki touched something in people already extremely committed to music education for children. He was truly a spark that lit a flame and music education is forever changed as are we all.

-

John Kendall saw what the Suzuki method could be and was largely responsible for bringing it to the U.S. and disseminating the information. Thanks also goes to Mrs. Waltraud Suzuki, who convinced her husband Shinichi to respond to Kendall’s letters!

-

William and Constance Starr took a huge leap of faith, taking their entire family with eight children to Japan for 14 months. Bill’s relationship with Suzuki and his interviews with him, the fact that Bill and Connie were able to observe their children’s lessons, and Connie’s study of Suzuki piano teaching made a big impact on the Suzuki world because of their ability to convey it all to us.

-

Despite some leading musicians who expressed doubts about the method early on, Suzuki’s vision drew in a particular group of forward-thinking teachers who not only were already wonderful players and pedagogues, but who decided to jump all in to what Suzuki was teaching, and not eliminate specific parts of the method.

-

And finally, the American Suzuki Institute at Stevens Point, created by Margery Aber, gave the structure needed for the SAA to be born.

Thank you to these amazing humans, and many not mentioned, for giving us all this gift.”

-Carrie Reuning, viola teacher, violin Teacher Trainer; Sandy Reuning, violin teacher, past president and Board member of the SAA

“Do you remember the statement, “Suzuki has changed my life”? In the early years of learning and absorbing Dr. Suzuki’s teaching, this was a statement uttered so often by many of us. I don’t hear this now. I assume this is because of the acceptance, awareness, and success of Dr. Suzuki’s philosophy and method in our own teaching over the last fifty years. Can you fathom what would have been the norm for music education without Dr. Suzuki’s influence? The SAA began that task of educating us all about Dr. Suzuki’s undeniably successful teaching strategies over 50 years ago.

Let me go back to the mid-sixties and expound on my hero, Professor John Kendall. He was the first music educator from the United States to travel to Japan with the sole purpose of learning more about Shinichi Suzuki. Kendall wrote articles, published three volumes of violin books based on Suzuki’s method, and worked alongside others to bring Dr. Suzuki and his Japanese American Tour Group to the United States. These children left us all with gasps of amazement—their performances were marvelous, especially as they were so young. Without Kendall’s unparalleled efforts, it would have been difficult to imagine Dr. Suzuki’s success in Japan here in the United States. Soon after this awareness, many American music teachers traveled to Matsumoto, Japan to observe and to study with Dr. Suzuki.

I met Professor Kendall when I accepted a teaching position in the schools in Alton, Illinois, and began a night class that he taught. That is when I said, “John Kendall changed my life.” I continued my work with Kendall completing my master’s degree with an emphasis on the development of Suzuki cello materials for Book One.

Moving forward, another pioneer in the development of Suzuki training in the United States was Margery Aber. Dr. Suzuki suggested to Aber that she should offer a Suzuki summer camp in the United States as had been done in Japan. Aber founded the first Suzuki institute in Stevens Point, Wisconsin, in 1971. I was asked to be the first cello teacher at that institute, and Jean Dexter joined as first a graduate student assistant and then the second cello teacher. We taught 14 students our first year and doubled that number the next year. The Stevens Point Institute was the beginning of a serious awareness of Suzuki education in the United States.

In the night hours of Stevens Point over several years, many of the cello teachers created the cello books. We hoped these books would follow the step-by-step method Dr. Suzuki had written for the violin. Soon, Yvonne Tait, retired professor, and Suzuki cello teacher, was asked to be the head of the Cello Committee. Our three volumes were ready to be shared with the Japanese cello teachers. Over the last fifty years, ten books were published with the help of teachers in Japan. The tireless efforts of so many cello teachers to prepare these books must be listed here in this article. I apologize for any names I have left off the list. Barbara Wampner and Tanya Carey have carried out this process for most of these 50 years. Please also give thanks to the following people for their tireless work: Jean Dexter, Nel Novak, Gilda Barston, Carol Tarr, Catherine Walker, Carey Hockett, Rick Mooney, and Yvonne Tait; our colleagues from Japan, Valclav Adamira, Akira Nakajima, and Mr. Nagase; from Europe, Anders Gron. All these cellists made it possible for the cello materials to be the backbone of early cello instruction throughout much of the world. None of them received royalties for the original publications and revisions.

The SAA has given us all an opportunity to share our teaching experiences through Teacher Training, international institutes, conferences, and the American Suzuki Journal. We are proud of our thousands of cellists, who are products of Dr. Suzuki’s philosophy and method.

The SAA’s most valuable contribution, in my opinion, has been the Teacher Development Program. It’s evolved a lot over 50 years, but the values of life-long learning with excellence in a nurturing learning community are hallmarks. This program has been largely responsible for the growth of Suzuki-trained musicians in the Americas. These values have also influenced the training of music educators at the university level.

In the early days, the first Teacher Development Committee decided not to do an exam at the end of the course and issue a certificate for those who passed. The committee believed that giving a certificate would have been in opposition to the life-long learning that Dr. Suzuki espoused. After all, teaching is a skill that takes repetition and reflection, just like practicing our instrument. The SAA guidelines, following Dr. Suzuki’s example, encouraged us to always look for how to improve ourselves so that we can better meet the needs of the family before us. This lifelong quest for excellence has set us apart.

With the pedagogy and performance descriptors, we have taken the “mystery” out of how to describe good teaching and performing, and how to assess it. The SAA has developed courses that teach content and courses that teach us how to evaluate and receive feedback for our teaching. Each of us can plot our teaching excellence at some point on a bell curve. If lifelong learning is our goal, then the hope is that, in this nurturing environment, each of us will strive to move one or more notches to the right on that curve.

The SAA has encouraged that nurturing community that we’ve developed in our studios to be replicated with colleagues at conferences and institutes. By design, courses are required to have a meal together. Conferences have receptions and social times where we can share our successes with colleagues as well as get new ideas for an area that we want to improve. We eagerly share our teaching “secrets,” something that was not the norm in the early days. These are just a few examples of how the SAA has endeavored to preserve and to pass the legacy of Dr. Suzuki to the next generation, and I believe they have influenced music education as a whole.”

-Marilyn Kesler, cello Teacher Trainer, past Board member of the SAA

“The SAA’s most valuable contribution, in my opinion, has been the Teacher Development Program. It’s evolved a lot over 50 years, but the values of life-long learning with excellence in a nurturing learning community are hallmarks. This program has been largely responsible for the growth of Suzuki-trained musicians in the Americas. These values have also influenced the training of music educators at the university level.

The SAA was four years old when I came on the scene in 1976. I still remember taking my first teacher training course at ASI. At that time, there wasn’t a syllabus for each book—there weren’t even unit courses. All the teacher trainees were gathered for a meeting. If it was your first time at ASI, you followed a faculty member to your room and began with the philosophy. Then the trainer would teach the pre-Twinkle steps and proceed through the book to as far as the class could get. If you had previously attended, there was a quick review of what the group knew, and then the class proceeded from that point covering as many pieces as possible in the week. There were no guidelines for the number of people in the course, the number of hours classes met, or what should be covered. The only instrument for which there was training was violin. Eventually, cello and piano were added, and now the method has been adapted for 15 instruments.

In the early days, the first Teacher Development Committee decided not to do an exam at the end of the course and issue a certificate for those who passed. The committee believed that giving a certificate would have been in opposition to the life-long learning that Dr. Suzuki espoused. After all, teaching is a skill that takes repetition and reflection just like practicing our instrument. The SAA guidelines, following Dr. Suzuki’s example, encouraged us to always look for ways to improve ourselves so that we can better meet the needs of the family before us. This lifelong quest for excellence has set us apart.

With the pedagogy and performance descriptors, we have taken the “mystery” out of how to describe good teaching and performing, and how to assess it. The SAA has developed courses that teach content and courses that teach us how to evaluate and receive feedback for our teaching. Each of us can plot our teaching excellence at some point on a bell curve. If lifelong learning is our goal, then the hope is that, in this nurturing environment, each of us will strive to move one or more notches to the right on that curve.

The SAA has encouraged that nurturing community that we’ve developed in our studios to be replicated with colleagues at conferences and institutes. By design, courses are required to have a meal together. Conferences have receptions and social times where we can share our successes with colleagues as well as get new ideas for an area that we want to improve. We eagerly share our teaching “secrets,” something that was not the norm in the music education world fifty years ago. These are just a few examples of how the SAA has endeavored to preserve and to impart the legacy of Dr. Suzuki to the next generation, and, I believe, have influenced music education as a whole.”

-Patricia D’Ercole, violin Teacher Trainer, past Board chair of the SAA

Defining the organization

“My most intense involvement with the SAA was in the 1990s. This was a time of change and challenge within the Association. At its lowest point, the SAA faced dismal fiscal circumstances and the loss of its executive director. We were incredibly fortunate to have found Pam Brasch to assume the directorship—it was not an easy position to fill. Pam’s wonderful organizational abilities, fiscal sensitivity, patience, consistency, and genuine kindness were critical in setting and maintaining our path forward.

We needed to ensure the organization’s structure reflected accepted national norms for professional nonprofits. This was an essential step to moving forward before we could seriously address our fundraising needs and have a chance to appeal for support from businesses and foundations. The Association received a major development grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to support a series of trainings in nonprofit organizational structure and fundraising. During this time of reflection and planning, the Board also read The Fifth Discipline by Peter Senge and Even Eagles Need a Push by David McNally, and regularly consulted a series of practical guides created by the National Center for Non-Profit Boards (now “BoardSource”).

Concurrent with my work at SAA, I was also selected to be a fellow in the Kellogg National Fellowship Program. I received training in Dr. Peter Senge’s cutting-edge work on the creation of learning organizations, defined as “a group of people who are continually enhancing their capacity to create the results they want.” I shared numerous experiential training activities with the Board to assist in our understanding of the basic leadership skills needed to develop a healthy organization. Subjects included personal mastery, mental models, shared vision, and team learning. This emphasis on team learning and leadership was a natural match with the Suzuki philosophy and inspired many of our conference and meeting themes as we sought to “Create Learning Communities.” In addition, the Board became more aware of the concept of the “servant leader,” an approach that highlights the value of being a role model, taking risks, promoting others, initiating action, giving rather than taking, and listening rather than talking.

We spent extensive time working together to create a vision, mission, and detailed 10-year Strategic Plan. As a part of this process, we conducted membership feedback surveys along with information update sessions at summer institutes (this was a pre-Zoom world). The Plan included the following areas of focus: Ongoing SAA programs and services, communication and networking, teacher development, Suzuki outreach, research and evaluation, parents, conferences, special events, and organizational development. To assure the Plan was addressed, action plans were created that included: deadline dates, names of specific projects, specific tasks (or “small steps”), responsible persons, date completed, and comments. The Plan was ongoing and expected to be reviewed and adjusted as needed. The entire Board and staff participated and were very involved with the implementation of the plan. This was a “hands-on” Board.

The Board intended to provide the Association greater stability while also allowing flexibility. A better-educated Board could adjust its own makeup in a timely manner to specifically address the Association’s changing needs as it dealt with the strategic plan. A future Board could include both elected and appointed members, in a change from the previous elected-only membership. Officers were also drawn from the Board itself, rather than the previous tradition of electing officers from the general Association membership—to assure the new officers had a solid understanding of the issues at hand. The Association created a much-needed document that defined the expectations and qualifications of being a Board member. As a means of enhancing the Association’s image to the general public, a new Honorary Board was created consisting of accomplished professionals from a variety of fields including concertmasters, nationally recognized childhood educators, and entertainers. Their input was also sought as needed, to provide additional perspectives to the Board.

Fundraising training set goals in three-month intervals. The Board and staff contacted potential donors, created incentive packages for businesses, increased the number of conference vendors, developed their ability to spread excitement about the SAA in short “elevator speeches,” and increased membership in the SAA and its list of potential donors. An annual fundraising plan was created and implemented with cash matching incentives as well as new donor recognition levels for long-term donors.

The SAA leadership training retreats were designed to assist in building a cohort of future leaders and support current leaders. The retreat in Estes Park, Colorado (1995) included Teacher Trainers, institute directors, conference coordinators, state/local/provincial representatives, and anyone else interested in leadership. Sessions included: keynotes from leadership and organizational experts, instrument breakouts, conflict resolution training, marketing your program, fundraising, grant writing, recruiting volunteers, Feldenkrais sessions, and Brain Gym sessions.

During this time, there was also a rigorous, detailed study of the Teacher Training and the application process used to identify new Teacher Trainers. This took place over several years and included numerous feedback opportunities from the Trainers and the membership, as well as guidance from outside experts. A new Ethics Statement was also created.

One of the major highlights and privileges of my life was to work with the Board, Teacher Trainer Teams, and SAA staff. This was a group of people willing to be honest, question, and celebrate—all within the context of furthering the vision and mission of the SAA.

-Jeffrey Cox, violin and viola teacher, past president and Board chair of the SAA

“In my Unit One training courses, I often ask participants this question: What is your recollection of the first time you heard about the Suzuki Method? The answers are always

as varied as the individuals in the class. For some, the method was woven into the fabric of their family, so they have no real memory of the first time. Others may recall hearing about other students who studied Suzuki when they were growing up, but didn’t really know what that meant. And still others may have heard disparaging remarks about students who don’t read or other lingering rumors about the method.

I vividly remember the first time I heard about this remarkable approach to teaching music. I was a freshman clarinet major at Western Illinois University. Doris Preucil was my instructor for the violin methods class I was required to take. She had so much enthusiasm for the method. I was fascinated by the results she was getting and asked if I might join her pedagogy class.

Looking back, I realize what an incredible opportunity this was for me, as formal teacher training would not become available to teachers until the SAA created this program. This training program has been the SAA’s most important and substantial contribution to the world of string teaching.

As I became more involved in the method as a young teacher, I often met resistance from traditional youth orchestra directors, traditional public school teachers, and university professors. All of these people couldn’t deny the tremendous talent that had been developed in Suzuki students, but they didn’t understand how the method worked and found it suspect. “There must be some trick,” I remember one teacher saying upon observing a very young student playing a masterful performance of Mozart A Major.

Through ongoing SAA training opportunities for our teachers in university settings, in apprenticeship programs, in the short-term Unit courses offered at Suzuki summer institutes, and most recently online, we have pulled back the curtain and made the essence of Suzuki teaching more understandable and attainable to teachers who are interested.

Now, some fifty years later, I realize we have not only changed the minds of those critical university professors and public school teachers. Those conservatory teachers often were themselves Suzuki students and, they seek out the method for their children.

Another way that the SAA made our work visible was through the many masterclass teachers who were invited to teach at our Biennial National Conferences. I distinctly remember having lunch with Dorothy Delay in the dining room of the conference hotel. We were surrounded by tables of Suzuki teachers, each one engaged in lively conversation about teaching and demonstrating bow holds on a fork or spoon. Ms. Delay looked around that room and with a tear in her eye, said. “This is the future of music education in America. In my world, everyone teaches behind closed doors because we are all in competition with each other. But this is extraordinary.”

The movements for racial justice alongside the Covid-19 pandemic gave our members the opportunity to pause and reflect on what our future will look like. We have more work to do making sure that the Suzuki Method is available to all children and teachers. Shifting our Teacher Training into the new frontier of the internet has finally brought access to teachers who previously could not afford the time and money to become trained. I sincerely hope that the SAA and the Suzuki Method will become leaders in the world of online training for the next 50 years. Congratulations to all of my colleagues, past and present, SAA staff, and leadership for the amazing place we hold in the world of music education.”

-Edward Kreitman, violin and viola Teacher Trainer, past Board member

Carrie Reuning-Hummel began the study of the violin at the age of five with her parents, Joan and Sanford Reuning in Ithaca, New York. She was one of the first Suzuki students in the U.S. and studied with Shinichi Suzuki on numerous occasions. She is director of Ithaca Talent Education and heads the master’s program in Suzuki Pedagogy at Ithaca College.

Sandy Reuning is the director of Ithaca Talent Education and an adjunct professor at the School of Music, Ithaca College. He is coordinator of the master’s program in Suzuki pedagogy and director of the Suzuki institute. Sandy is a past president and board member of SAA and currently serves on the violin committee. Sandy and Joan’s association with the Suzuki movement began in 1964 after hearing the Japanese Tour Group in Philadelphia, and their students were used for demonstration by Dr. Suzuki at workshops at the Eastman School of Music and Syracuse University between 1966 and 1969. In 1974 they went to Japan and studied with Suzuki, and Sandy has made numerous return trips. Sandy was on the faculty for the 1978 International Suzuki Conference in San Francisco and the 1999 conference in Matsumoto. He was director of the Friendship Concerts of 100 Japanese and 100 American students in 1987 and chairman of the 1981 International Conference in Amherst, MA.

Marilyn Kesler has recently retired after 42 years as a teacher in the Okemos, MI, Public Schools, teaching seventh and eighth grade strings and three high school orchestras. She is continues to be the director of the Community Education Suzuki program where she teaches Suzuki cello lessons.

Ms. Kesler earned a master’s degree in music education at Southern Illinois University where she specialized in the adaptation of the Suzuki violin method for the cello with John Kendall. Her undergraduate degree in music education was from Indiana University where she studied cello with Janos Starker and Leopold Terraspulsky.

Patricia D’Ercole is a Suzuki violin teacher and teacher trainer. She did long-term training with Margery Aber and studied with Dr. Suzuki. She has been a clinician in 23 states and 7 foreign countries. Pat has written numerous articles for the ASJ, was chair of the SAA Board of Directors, and a member of the Every Child Can! and Suzuki Principles in Action Committees. She was the founding president of the Suzuki Association of Wisconsin and has been co-coordinator for the International Research Symposium on Talent Education since 1995. Through her leadership, a collection of videos which chronicles Dr. Suzuki’s teaching at the American Suzuki Institute in 1976, is now preserved on the web. Pat created the UWSP Suzuki Strings Mentoring Program, a year-long online practicum for Suzuki teachers. Most recently, Pat is the Director Emerita of the Aber Suzuki Center at the UW-Stevens Point.

Jeff Cox received a B.M., M.M. from Eastman and an M.M.A., D.M.A. from Yale—all in violin performance. Principle instructors: Doris Preucil, Millard Taylor, Broadus Erle and Syoko Aki. Member first Graduate Quartet in Residence at both Eastman and Yale. Faculty member at Central Washington University, Texas Christian University and Professor and Chair at the University of New Orleans and the University of Massachussets/Amherst. Founder of Washington State Suzuki Festival, Co-Director of the TCU Suzuki Institute. Teacher Trainer (ret.) and former President/Chair of the SAA. Received award for “Outstanding SAA Leadership” from the SAA. Selected as a Fellow for the Kellogg Leadership Program which included educational travel to Costa Rica, Guatemala, Israel, Egypt, Spain, The Netherlands, Poland, Hungary, The Czech Republic and India. He also worked as a consultant/trainer for several LGBTQ organizations in New Orleans.

Edward Kreitman is the founder and Director of the Western Springs School of Talent Education and the Naperville Suzuki School. Mr. Kreitman received his undergraduate degree from Western Illinois University where he studied Suzuki Pedagogy with Doris Preucil and Almita Vamos. In 1986 , he studied with Dr. Suzuki at the Talent Education Summer School in Matsumoto, Japan.

Mr. Kreitman has served the SAA in many capacities including a member of the Board of Directors, Violin Committee, Teacher Development team and as Coordinator for several National Suzuki Teacher Conferences. Edward Kreitman enjoys an international reputation as a registered Teacher Trainer of the SAA and is the author of "Teaching from the Balance Point: A Guide for Suzuki Parents, Teachers and Students" and "Teaching with an Open Heart: A guide to developing Conscious Musicianship." Edward Kreitman was the 2019 recipient of the IL ASTA Studio Teacher of the Year Award.