IMG 4641

I watched with my wife and three children from the pews of the old church in the small village of Dale, Indiana, a stately but modest wooden structure with a steeple, painted in white, on a quiet street, like a post card.

My daughter, Arielle, eighteen years old, was readying herself for what would be her final recital as a member of “Strings,” the Suzuki organization of teachers, parents, and young students that is and has been the center of the violin universe in the area; indeed, it is this fine group that my family, including each of my four children, has been so intimately involved with for a decade and a half, coming together for lessons and recitals just like this. The spring recital in May has long been a gratifying exercise, a yearly ritual and learning method, and a pleasant prelude to summer’s beckoning call.

And, indeed, it was summer, which was to say, Vivaldi’s “Summer,” that now occupied Arielle’s energies and attention.

Accompanied on the piano by Suzuki instructor Ann Brown, her teacher of fifteen years, Arielle was engaging the piece with vigor and precision. Her bow moved rapidly, as she fingered the strings, her two hands working feverishly in tandem, creating the brisk but rousing pitch and resonance that characterized this wondrous composition, evoking by sound the image and sensation of a gathering and violent tempest, whipping through the electric atmosphere of a steamy, summer day.

I observed proudly as she sprinted musically through the sections, artfully bending the rebellious notes to her will, persuading them to merge, divide, and reform as the piece demanded, bringing intensity, passion, and expertise to the hard-charging and powerful opus created centuries before by the great Vivaldi.

So immersed in the music was Arielle, so absorbed in its riveting translation, she seemed to become the piece for these moments, embodying it, as it were, by osmosis and alchemy, a micro-whirlwind on stage, hurling thunderbolts and bluster, barely containing the energy.

As the final notes leaped forth and ceased as echoes, she beamed contentedly as if an athlete after a contest, consumed but satisfied by her performance.

The audience acknowledged her approvingly as the applause filled the chamber and Arielle took her bow, her final bow after so many years and so many recitals, before her Suzuki friends. Some in the house had followed her career and knew how long it had been—most of all, her teacher, Ann.

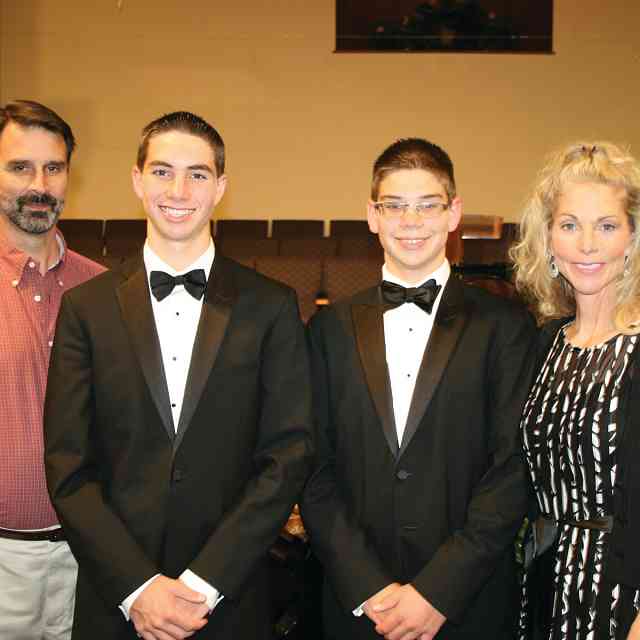

Arielle with he younger sister, Dr. Moss, and Ann Brown, her Suzuki instructor of 15 years

I had written earlier, in fact thirteen years ago, in the American Suzuki Journal, about my daughter and my attempts to convince her to practice her violin at the tender age of three. I recounted somewhat whimsically about the challenge of getting a three year old to master anything, let alone something as complex and challenging as the violin. I wrote about my hopes for my daughter, my wish for her to “cultivate a special talent early in life,” for which the violin seemed perfect. I mentioned that I liked the Suzuki method, which helped kids master musical instruments the same way they learn to speak: by listening and practicing. I also wrote that Ann, the instructor for the local Suzuki group in Jasper, Indiana, known as “Strings,” expressed concerns that Arielle was, perhaps, too young and that we might become frustrated, that she was the youngest student Ann had ever taught. I wrote also that despite our best efforts, Arielle refused to play. I mentioned how over the course of several months, I employed any number of strategies to motivate her, none of which worked—nothing, that is, except the practical, common-sense suggestion given by Chee Yun, a world-renowned violinist who had just conducted a master class with the Strings kids in Jasper while on tour in the Midwest.

I had nervously asked Chee Yun what to do with my little darling who would not practice her violin. She delivered a one-word answer that changed the trajectory of Arielle’s musical career:

“Bribery,” she declared emphatically.

She elaborated further: “Make it fun. Give her a treat. Reward her with something when she’s done.”

She reassured me further that after a time I would no longer have to bribe her. “She’ll do it on her own.”

And so it came to pass. Between bubble gum, jellybeans, ice-cream, and the occasional trip to Dairy Queen for a Mr. Misty, I was able to persuade my three year old to play her violin. Life, indeed, as I had written, had become so much “sweeter.”

Well, a lot has happened in my daughter’s musical life since Chee Yun’s pearl of wisdom some fifteen years ago:

Arielle has garnered a gold medal each year since the sixth grade at the Indiana Solo and Ensemble, held the position of Assistant Concert Master in the Indiana All-State Orchestra, and won the Indiana State Federation of Music Clubs Competition, among many other achievements at state level.

Always eager to broaden her musical horizons, Arielle took up the piano at age six and the saxophone in the sixth grade. Through the years, she has also won a goodly share of gold medals at the state level in these instruments as well. As lead alto of the Jasper jazz and symphonic bands for three years, drum major and soprano sax soloist of the Jasper Marching Band for two years, she still managed to devote sufficient time and energy to become accomplished and competitive in each instrument.

Arielle regularly played for residents at a nursing home in Jasper, IN, as a volunteer

But it wasn’t all competition. She also provided musical entertainment on a volunteer basis for local festivals and events, community theater, and nursing homes. She has also been active in teaching other young students in the area.

It is fair to say that Arielle has built her young life around music; it has enriched her and exposed her to a wide range of rewarding experiences; it has provided leadership opportunities that have helped her grow and mature; she has also shared her passion and talent with others.

And now, fifteen years later, having completed all ten Suzuki books (two years ago), having won a cornucopia of gold medals at state level, and distinguished herself musically at her school, in the community, and around the state through a variety of instruments and competitions, what does Arielle want to do with the rest of her life?

Why, become an ophthalmologist and do humanitarian work in Africa.

She of course has my blessings; but I know that she will never forget music and that it will remain a positive force in her life, whatever she does and wherever she goes.

After Arielle’s rendition of Vivaldi’s “Summer” with which we began our story, Ann Brown, Arielle’s teacher of fifteen years, spoke about Arielle before the “Strings” family at the church in Dale, and retold the challenges of teaching a three year old, and, in particular, Arielle, who would not say a word or even look at Ann for their first five years together. It does seem like another age.

When she finished, she gave Arielle, formerly her youngest pupil ever, a warm hug and wished her well.

On that “note,” on behalf of Arielle and my family, I would like to thank Ann, Strings, and the Suzuki organization for enriching our lives so deeply—and for taking a chance on our little three-year-old, years ago.