What is your background with guitar? How old were you when you started and what attracted you to it?

It was the Beatles! I remember when I first heard “I Saw Her Standing There” it just hit me like a bolt of lightening! Love at first sight, once I saw a guitar, I just knew I had to have one. I was nine years old, and I started out playing a steel string guitar made of plywood. The action was really high, and I remember playing ‘til my fingers were bleeding.

Did you take lessons or study on your own?

I lived on a school campus in Connecticut called the Wooster School where my father was headmaster. It was a boarding school for high school boys, so I heard certain students playing and I was exposed to electric guitars and to their music.

A friend of my older brothers named Jeff Stout was, in many ways, my first teacher. We listened to records and figured things out—very much like early Suzuki learning. I was like so many at the time in a few bands and I’m still great friends with the members of my first band. In many respects those early “band” years were seminal to my creative outlook.

How did you learn about Suzuki guitar? Have you taught any Suzuki students in masterclasses or seen any Suzuki students perform?

My two children took Suzuki violin at The School for Strings. The experience was so positive that even though they no longer play the violin, I really think it was one of the better things my wife and I ever did as parents. I was really shocked because I knew nothing about Suzuki. Right from the start I was pretty impressed with the teachers.

I love all the group playing they do and feel this should be encouraged. Like many I’m sure, I have thoughts about what the future of the teaching could include.

The real person who really knocked my socks off in terms of Suzuki guitar was David Madsen. I have a bi-annual, one-day guitar festival called the Yale Guitar Extravaganza. I knew about David’s program and since my children were doing Suzuki, I thought I should have Suzuki Guitar at the festival. Now the Guitar Day at Yale always begins with David’s students and when I saw him working with them I thought, “Wow, this guy is a genius! He’s an unbelievable teacher.” He had a four-year-old play and then he presented a whole group.

Another influence was Norma McNamara. Norma invited me twice to do residencies at her studio—once in Utah and once in Kansas City. Norma absolutely inspired me. I just couldn’t believe the way she taught and all of the tricks that she had, like so many Suzuki Teachers have. And I came home a convert. At this same time I attended a Suzuki flute class by David Gerry whose wonderful and inspirational teaching reminded me of Norma.

Recently I have become friends with a teacher in New York, David Gonzales and have taught a few of his students in masterclasses.

How do you find the Suzuki students, generally?

In general, I’ve been really impressed with the Suzuki students in the following ways: they are always very prepared, they play through the piece very well and with a positive attitude. They seem to have no problem performing which says a lot about their training. I love all the group playing they do and feel this should be encouraged. Like many I’m sure, I have thoughts about what the future of the teaching could include. It should be as forward looking as possible and make the joy of music making a priority.

How and when did you get interested in composing? How did you pursue the interest and training?

From the time I picked up the guitar, I was always composing music. Most of my high school bands did original material. With one exception, I was not in cover bands and that I believe had an effect on my later musical life. I am not a great improviser, but I do have an improviser’s spirit. I have always been a “noodler” and I have always found the guitar and the fret board of the guitar to be a sea of wonder. I find constantly that it’s a magnificent place to get lost, and in getting lost, you find something—something that brings a certain amount of truth to you. The most bizarre combinations of notes can appear.

I have never really studied composition formally. I do bring pieces regularly to friends and other composers to get their opinions. I study and learn an enormous amount from the all the music I perform. For example, Benjamin Britten’s masterpiece the Nocturnal has been a constant composition lesson as well as all the Bach music I have recorded and performed. Composing is one of the most fulfilling and illuminating aspects of my life. In the act of composing I feel very present—the same way I feel on the best moments of performing.

Can you suggest any advice for young guitar students (and their teachers!) interested in getting into composition? What’s a good starting place?

Every year I have a seminar about Etudes with my graduate students at Yale. We discuss what we think an Etude should be and how they’ve influenced our lives. I ask them to compose an etude based on some deficiency that they have. Often it ends up being on what their strength is because they know they have to get up and play in front of everybody!

Everybody has something to say. We all have some sort of music in us that wants to come out. Every year there is somebody who didn’t know they were a composer, and when the assignment is done they say, “I just loved it! I’ve just got to write!” So, I would suggest in the beginning to write a model piece, in this case a model of an etude or a short piece you love. No more than a page or less perhaps to begin with.

Teachers can be of help in this area by discussing the form and phrasing of what ever piece they give to their students from the beginning. In this way the student gets to see how a piece is composed and will be perhaps write some thing similar say ina simple a,b,a form.There are as you know, tons of comparisons you can draw between movies and paintings concerning form for a start.This can help demystify the compositional process and inspire the student to say as I did” hey I can and want to do that!”

So, when you write it is with the guitar in hand and later you write it down? Do you take this approach with your students also?

I normally do compose with the guitar in hand and then write but immediately not for example, the next day. Whatever method you pick to write is fine with me because in the end it’s what you’ve composed that’s important not particularly how you did it.

I urge my students to write their etude down or at least record it with phrasing, dynamics and articulation.They must bring it to some sort of conclusion. Many people have trouble finishing pieces some times because of a psychological block or fear. They’re afraid of not meeting their standards or that once it is written it will be judged in some way.

It’s easy to have a bunch of ideas, but it’s important to complete them. If you can’t write it down, do your best to try because that’s a very important skill to have. You can bring it to your teacher and not be afraid of having an improper rhythm or something you need help with. My advice would be to jump in and then play it for people. Share it because it really will change your life.

You’re a great teacher, a composer and a great player. How do you balance it all?

Well, thank you, I appreciate that. I think you have to be somewhat philosophical about it all and open. As humans, we have choices about what we do and say. If you choose to have a family, I think that’s got to come first. If you choose to have children, between you and your partner, you’ve got to discuss your dreams and aspirations realistically, realizing that everybody’s going to be happier if your home base is working well.

There was some dialog between my children and my wife Rie and I concerning practicing especially when they were studying violin. We talked about it and tried not make it a precious thing—like “Oh, don’t talk to me now I’m practicing!” I just got used to them interrupting me, and eventually, they just didn’t do it. Maybe the Suzuki lessons were helpful there. By practicing regularly and enjoying it you’re setting a good example for your children and students alike. At times, I found it a challenge to see if I could concentrate in the midst of the occasional madness! That having been said, if the house is burning down,it might be a win-win situation to stop practicing!!!

Family life is ridiculously rewarding and it doesn’t exclude practicing well. A lot of people have told me that they think they practice much better after they have children because they have so little time. They get better at goal oriented practicing.

In terms of composition, I’ve started a new practice of keeping a compositional journal. I write down ideas all the time and it seems I’m always kind of composing. Just the other day I was teaching a Brouwer Sonata and I thought, “Oh, I can use that!” So, I made a note—Brouwer Sonata, whichever line, check it out later for a reference, for some inspiration and rubbery!

As far as the schedule, I’ll tell my manager, like I did recently, “Don’t accept anything for this month,” and during that time I concentrate on composing. With composing, it’s pretty much ideas going around the clock, but then I set aside time. The last few pieces I wrote was a big piece for David Russell and a duo piece for steel string guitarist Bill Coulter and I. I don’t write a lot and it can be frustrating when the urge hits hard and there just isn’t enough time.

Another point of concern is learning new repertoire. I don’t have a huge repertoire. That’s mostly because I write and because I’ve taken a fair amount of time to be with my family. Now my children are older so I have more time. I don’t think it’s the time for you to do all the Bach Cello Suites and Lute Suites plus 18 Concerti when you have two small children. It’s just a bad idea. You can still play; you can still set goals for yourself. It doesn’t mean you have to shut down. You just have to be realistic and happy you can play at all!

I know many teachers with full schedules who find it difficult to get any personal practicing in. Can you offer any advice or insight on that?

It’s very important for people to know what makes them happy. Most people who go into music really do actually like to practice. They like the feeling they have after practicing an hour or three hours. It’s a fantastic feeling to be in shape, you know? If you know that about yourself you’ll realize, “I need this amount of hours,” then you can work that out. My wife and I used to have sessions, which I loathed, about planning out the week. I’m more of an improviser, a “Don’t-Box-Me-In” person. But everything went smoother because we planned. I could see look at the schedule and see I’d have to practice between this hour and this hour and just do it. That’s what we did in college, why shouldn’t we do it as adults? You had to practice a certain time; you had to get papers in, so you did it. You don’t leave things to chance.

I think another part of the balance is realizing that you have limitations; everybody does. I think most of us want to be perfect at everything. Sometimes you’re going to be a really good dad, and sometimes you’re not going to. Sometimes you might play a concert that you’re really pleased about, but sometimes you’ll do your best, but it wasn’t the greatest concert.

So, I think it’s just trial and error and beating your self up less! After a while you’ll see what works and what doesn’t. Then it’s up to you to make the choice to be just a little bit more disciplined. Many of us don’t want to do that. It is a struggle but as they say, “once you make a choice you’re free” and you’re always happier. If you don’t do your schedule, if you don’t say, “I need to practice two hours a day,” then you really will build misery into your relationships. You’ll most likely have arguments with people because you’ve pent up all this frustration from not doing what you actually like.

And that’s part of having a home life that works. My family knows that I’m crabby after a few days if I don’t practice. I mean, I take my guitar on vacation. I just like it. I like to practice on vacation; it fun for me! I don’t like a vacation without a guitar. It’s not as fun. That doesn’t mean that I’m playing all day either.

One of the things that used to drive my wife crazy was she would make dinner and she would say “dinner ready in 5 minutes” and I would keep practicing. I’d say, “I’ll be there in 5 minutes! No, I will!!” And I realized to myself, “you know, you’ve got to stop now.” It’s the little selfish things we do that irritate everybody. In the long run you have greater happiness in the above situation by putting down the guitar and going to dinner and you’ll be less hungry! So you can try to please others selfishly, you’ll be better off. Does that make any sense?

Well, these are some good ideas. Do you have anything to say in conclusion?

I think people should have more discussions about burnout. Teachers can get burned out teaching. Many, many of us do. One thing I finally have learned is that I know my limits most of the time, not always!

We also ought to perhaps have seminars about how to manage finances. Everybody’s got bills to pay. Yes, we love teaching, we love the guitar, but we also get paid to do it. What happens is we forget that as musicians, unless we’re superstars, we earn a limited amount of money.

I have a friend who was a businessman on Wall Street. Years ago he took me aside and said, “You know, you lead your life really irresponsibly financially.” Most guitar teachers—some, not all, but I was one—need to think about your life financially and try not to live beyond your means. It would be great if at an early age people really understood that, as painful as it is for musicians. Most of us just don’t want to think about that, but then you get to be 40 or 50 or when you want children, you really pay for it. You have credit card debt and that affects your teaching because you take too many students. Taking on more than you can handle is a problem. Generally, I see people most frustrated in their late 30s and 40s, and they can become bitter.

Not everybody will have a solo career, but that doesn’t mean you can’t be successful. I know many people that play wonderful concerts in a variety of venues. They may not be playing at Carnegie Hall, but they keep growing as musicians. It’s important to realize, as you get older, it’s not easy to practice late at night. Your body changes and it’s hard to practice; it’s a physical activity. So that goes along with burnout—with teaching too many students and not wanting to practice. It’s totally understandable that you don’t want to be like Tarrega who apparently put his feet in the ice (or whatever he did) to keep himself up late at night to practice.

So, burnout should be addressed because we all just want to forget that we do get burned out and that we do need vacations. Sometimes we have a hard time saying “no.” When a parent calls and says, “Oh, my son loves the guitar and you’re such a great teacher …” you have to say, “No, I’m sorry, my schedule is full. I can’t do it.” Even though part of you says, “I need that extra money for … ” You can say, “For the next two years I will teach more than I usually do because I need the money, but then I will cut back.” Enforce limits.

I think we should have more open discussions about these topics, and by doing so we will become better teachers and maybe happier!

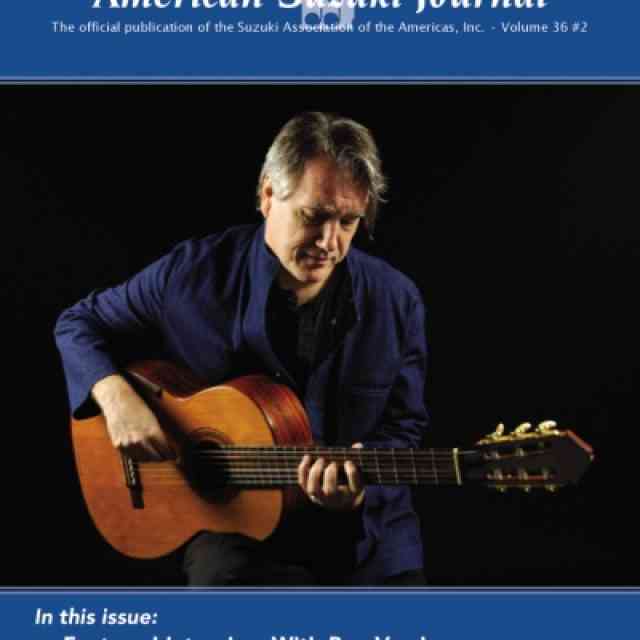

Excerpt only. Read the complete article in the American Suzuki Journal.